You may have heard of automatic writing—the practice of writing freely, usually by hand, without thinking. It’s a technique with spiritual roots and associations, and advocates of automatic writing believe that when we tap into our unconscious mind, we can write freely and intuitively without judgment. We aren’t controlling the work as much as channeling it. We’re medium and muse, all at once!

It’s not for everyone (though it can be interesting to give it a try!)—but there are other ways for writers to utilize the unconscious mind to elevate their craft.

In this article, we welcome The Novelry graduate Shylashri Shankar, who generously explores her own experience of writing from the unconscious mind to find guidance with her fiction.

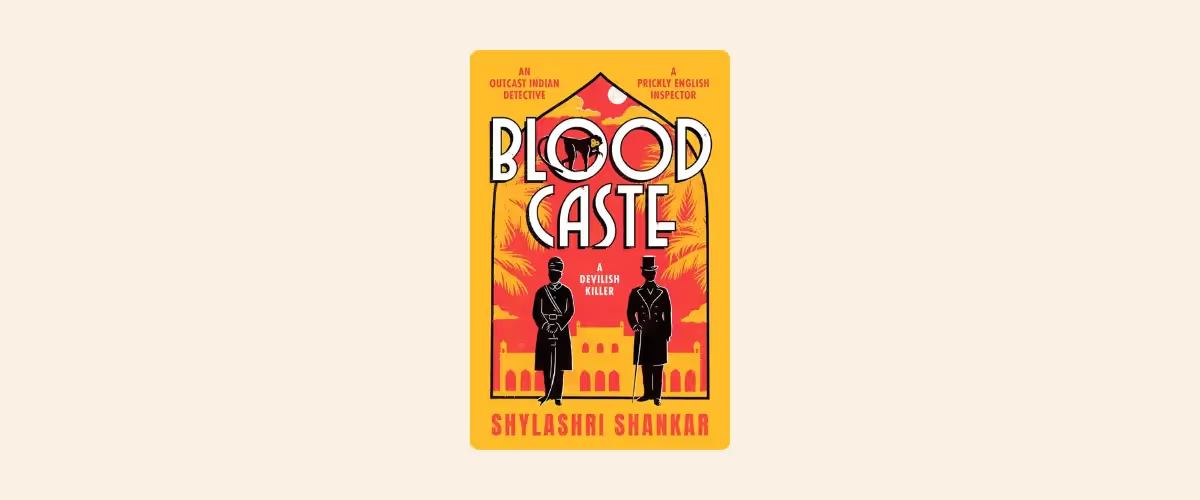

Shylashri took The Novel Development Course and The Ultimate Manuscript Assessment at The Novelry, and was introduced to her agent James Wills at Watson, Little through our bespoke submissions service. Shylashri’s novel Blood Caste was acquired in a three-book deal by Canelo Crime, and will be published tomorrow!

Why not try some of Shylashri’s techniques? You, too, might be able to access a new level of writing wisdom by tapping into your unconscious mind...

The conscious mind of the writer

I don’t know about you, but all I feel is pure envy when listening to J.K. Rowling on how she gets her ideas. ‘There is a lake, and there is a shed by the lake,’ she says. ‘The lake throws me the stories, and I catch it and type it up in the shed.’ Other bestselling writers talk about the stories being dictated to them from the ether. How easy it all sounds! Why on earth do I have to struggle so much to find the voice of my story and its characters? How in god’s name do I tap into that dictation?

The unconscious mind of the writer

The unconscious, it seems, is where we must lodge this appeal. Every living creature possesses the unconscious. For us writers, this is the well of creativity brimming with the wildest, wackiest, and the most gut-satisfying stories. It is where our questions about what to write and how to inhabit our characters are answered.

It took me a decade of slogging over half a dozen novels (all locked up in the drawer) and filling notebooks with over a million words to realise that the unconscious is a realm not of words, but of tone, a feeling, a slant of the mind. Virginia Woolf calls it the rhythm:

A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it.

—Virginia Woolf

But this rhythm was a foreign land to me, someone who uses words to paper over uncomfortable emotions, and who crafts fine sentences that glide over the surface but never quite capture the emotional intensity.

The question I faced was: how can I connect with something that cannot be viewed with the thinking mind, rationally, logically, causally? The unconscious, I have come to realise, has to be felt with the body. You must learn to recognise the rhythm. Only then can you find and make the right words.

{{blog-banner-11="/blog-banners"}}

Three ways to open up the creative mind

Three techniques have set me on the path:

- Meditation

- Using an alternative therapy mode

- Journalling in a very specific way

Meditation

To connect to the unconscious, you need to be attentive, but not in a narrow way, which is what we are used to doing while learning a craft and in our everyday affairs. Narrow attention selects what serves its immediate interests and ignores the rest. But to feel the tone and the shape of emotions, the nudge of an attitude, the feel of a story, you need a broad kind of attention. For instance, your memory of how you felt in a childhood home is not conjured from physical details; it comes from a feeling. It is the type of attention, as the renowned psychoanalyst Marion Milner says in A Life of One’s Own, where you attend to something and yet want nothing from it.

Meditation enables this type of detached and wide attention. When Covid struck, I joined an online meditation group and began a daily practice, starting with 15 minutes and slowly building up to an hour. At the start of the meditation, I tell myself:

I am where I have to be right now. There is nothing I need to do.

Wide attention in meditation is a process of widening perception. You notice all the sensations in your body and broaden your body’s gaze beyond the room you are in, to the garden, the road, the bird calls, the sound of the wind and the trees, the honks from the cars, the rattle of wheels on asphalt, and so on. As you do so, you will find yourself relaxing and finding the rhythm. The more you relax, the more you will connect with the unconscious—a landscape that is wild and intense and never responds to control. Only to us letting go.

Even if meditation is not for you, nature can help. Try a walk in the park or even simply sitting in your garden or on your verandah to experiment with wide attention.

Therapies

It took a long time for my rational mind to understand that sense had a different meaning in the unconscious realm. We are told to give space to the reader to make meaning, but to do that, the writer has to understand that sense-making is experiential. We are forging a connection with the reader’s body, with their unconscious.

Therapies like the Body Code, the Emotion Code, and Internal Family Systems delve into such spaces, seeing the universe, as physicists do, as a range of vibrations and energies.

The therapist sets the intention at the beginning of the session. For a writer, it might be to unblock writer’s block, or be able to express a particular character’s voice more clearly. During the session, you work together to connect with different aspects of yourself you’ve either ignored or hidden away. This form of connection is used with a psychotherapy method: the Internal Family Systems therapy.

When a close friend from university became an energy healer, I decided to explore these therapies. I found IFS particularly useful because it identifies and addresses multiple sub-personalities within each person’s mental system. These sub-personalities consist of wounded parts and painful emotions, and parts that try to control and protect the person from the pain.

We writers are urged to dig deep into ourselves, especially the traumas and the associated memories. For a long time, though, I ignored the pain. I pushed it away and focused only on the positive; the protectors were doing their job, I suppose. What I didn’t realise was that I’d repeated that pattern with my characters. I defused conflict, never put them in any real danger, and made things easy and less emotionally fraught for them. It’s no wonder that for a long time, my main character remained a cipher—reserved, emotionally stunted, and coming across as banal and flippant.

Let me give you an example. In early drafts of Blood Caste, though my main character had been flung against a rock ledge in a fast-flowing river, not a scratch would I permit on my hero’s skin. Since doing these sessions and practicing meditation, I find myself less resistant to inflicting injuries—physical and emotional—on him and the other characters. I gave him deep gashes on his chest from the sharp rocks. Surprisingly, just inflicting this physical vulnerability unlocked some of my mental resistance (and my character’s) to pain, and let me dig into his (and my) emotional traumas.

Connecting to the painful parts also enhanced the wide attention I practiced during my daily meditation and helped me feel the rhythm of the story. None of it has been easy, not least because my self-explorations have been intense and highly uncomfortable. Though painful, the struggle has also been enriching: one where you learn and grow as a person and as a writer. Here, journalling in a particular way has helped me tremendously.

The unconscious, I have come to realise, has to be felt with the body. You must learn to recognise the rhythm. Only then can you find and make the right words.

—Shylashri Shankar

Proprioceptive journalling

Many of us have done free writing, where you sit down and keep your pen moving on the page, writing whatever comes to your mind. But focusing purely on reflecting the thoughts can sometimes put us into a loop of anxiety and even neuroticism. I did plenty of free writing, and many times found myself trapped in that loop.

Proprioceptive journalling is different from free writing. It is a form of meditation—of slowing down your thoughts and focusing on an inner hearing. The word comes from the Latin proprius, meaning ‘one’s own’. The creators of this method, Linda Trichter Metcalf and Tobin Simon, say:

Listen to your thoughts with curiosity and empathy and reflect on them in writing. But remember, you are searching for clues to the person you are, to the thinker within yourself rather than with the thoughts you are thinking.

—Linda Trichter Metcalf and Tobin Simon, Writing the Mind Alive

You start with noting down your thoughts (almost like free writing). If nothing comes to mind, then just write ‘nothing is coming’. There is no need to write fast, no need to edit, or think about punctuation and grammar. When you note down some thoughts, pick the one that calls out to you and ask the question:

What does it mean to me?

For instance, you may have written something about freedom. Then you can ask:

What does freedom mean to me?

Then write down whatever comes to your mind. If nothing does, you can repeat the question. In my initial sessions, I had pages of ‘nothing is coming’, but when I showed up every day and did it, things changed.

When you finish writing at the end of 25 minutes, ask yourself four review questions:

- Which thoughts were heard but not written down?

- How do I feel now?

- What story is it part of?

- Are any future story ideas arising from these thoughts?

Do this every morning as soon as you wake up. The practitioners suggest using Baroque music and candles to aid creativity. I have a mug of coffee and tend to write in a silence broken only by the sleepy chirrups of bulbuls and sparrows in the garden.

For us writers, this is a great way to explore the story and its parts. During each session, you can tackle a question from your work-in-progress. For example:

- How does your POV character feel about the situation they are facing?

- Where does the story go from here?

- What do they really feel deep down?

Later in the day, while composing or editing the chapter, you will find these journal entries a real boon.

Here is an excerpt from a journalling session where I felt my way to the theme of a work-in-progress:

It’s the pull and tug between being free and caging someone. Between putting some in cages to ensure order for others. It is the notion that one must conform otherwise you’ll bring chaos, and if you bring chaos, you must be caged and unfree, your freedom must be taken away. So order is paramount? But whose order?

—extract from the journalling practice of Shylashri Shankar

This style of journalling, I found, accomplished three things:

- It gave me a sense of play and freed me from expectations and deadlines since it was outside of my writing day.

- It made starting the day’s writing easier since I’d already explored a question connected to the scene.

- Even when I’m away from my desk, I get flashes of insights and images, and the story world seems much more real to me.

Alongside the journalling, I also practiced reading with my body. For a speed reader like me, it was especially hard. I returned to old favourites—Tolkien, Jane Austen, George Eliot, Arthur Conan Doyle—and read them slowly again. It can be even better to listen to them. Whenever you feel the sense of rightness—that’s the nudge from the unconscious—stop right there and ask why that is so. Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë, for instance, have an almost mathematical manner of sifting through the emotions all the way to the stand-off at the very core.

.avif)

Let the story flow

These daily practices have helped me recognise my own voice and pin down exactly what I want to say. Mind you, it doesn’t mean the sentences come fully formed, never needing an edit, or that there is no struggle to find the voice or to figure out the emotional dynamic. But once you find the rhythm, the story beats will flow with a luminous authenticity and a simple sense of rightness.

So, do connect daily with the unconscious, and you will ride the wave!

Blood Caste by Shylashri Shankar

Is Jack the Ripper at large on the streets of Victorian India?

Hyderabad, India, 1895. When three bodies are discovered with mutilations bearing an eerie resemblance to the Ripper’s Whitechapel victims, Chief Inspector Soobramania—known as Soob—is summoned to investigate.

Suspicion alights upon three powerful men: a Russian grand duke, an English earl visiting the city, and their friend, a Deccani noble, who is also the stepson of one of the victims.

Faced with the thorny imperial politics of accusing relatives of Queen Victoria, Soob must ally with his rival in the British Residency Police, Inspector Wilberforce, to hunt down the killer.

So begins a deadly game of cat and mouse played in the shadow of empire, where high birth protects foul deeds and where spilled blood counts for less than wealth.

Be sure to order Blood Caste, a richly textured and utterly compelling historical crime thriller from the dazzling debut voice of Shylashri Shankar, in the U.K. and in the U.S.A.!

Wherever you are on your writing journey, we can offer the complete pathway from coming up with an idea through to ‘The End.’ With personal coaching, live classes, and step-by-step self-paced lessons to inspire you daily, we’ll help you complete your book with our unique one-hour-a-day method. Learn from bestselling authors and publishing editors to live—and love—the writing life. Sign up and start today. The Novelry is the famous fiction writing school that is open to all!

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)