How do you make the important decisions when it comes to casting your novel? And how can you write – and track – compelling and complex character relationships? Writing a realistic scene or authentic dialogue between two characters can be tricky enough, but crafting believable character relationships can often feel like one of the most daunting parts of starting to write.

Whether you’re writing strained mother-daughter relationships, lifelong friendships or romantic relationships, putting such complexity of feeling onto the page, and making it serve your story, isn’t always simple – although it can be great fun!

In this article taken from one of the 100+ lessons of our Ninety Day Novel Class, our Founder and Course Director Louise Dean shares some handy hints and tips for deciding which characters must stay and which must go in your novel, drawing from her experience on creating her own character relationships.

Know the purpose of every character in your novel

To really get to grips with characters’ relationships in your novels, it can be helpful to start with the purpose that each person serves within your story.

Each and every character has a single purpose for the storyteller – and that is their role or agency vis a vis the moral development of the protagonist, hero or heroine, the subject of your novel. They either assist or hinder. The power struggles are a great well from which you can draw inspiration as you plot your story and map characters’ relationships.

Each and every character has a single purpose for the storyteller – and that is their role or agency vis a vis the moral development of the protagonist.

—Louise Dean

Who are the key players?

There are filler characters, the door holders, and bag carriers, the petrol pump attendants, and these too may have something to add. But as you begin mapping character relationships, you need to concern yourself with the players on your team first and foremost. Some 3-15 players.

What’s the nexus?

Wherever you are in your novel, you should be looking at the crucible – the hell Sartre might have dubbed it, or heaven – that is the nexus of character relationships. What people want from your main player and what he or she wants from them.

The relationships – the push and pull of their reciprocal wants and needs – will range according to the relationship status, from highly negative and reversing (antagonist) to assistance, affection, love and self-sacrifice (the friend or lover).

What do different characters want from each other?

So you’ll be playing these out in your story through conflict and clarification – questions posed by the other characters for your main player to answer, and assaults on their values or beliefs along with reassurance.

Find the conflict for believable relationships and interesting characters

Conflict contains the most energy to propel your main character through change faster. This is the secret to storytelling.

Certain characteristics of the protagonist and antagonist are revealed often only through relationships with each other or with circumstances (either external or internal) and events played out in action and reaction. Under the pressure of situations, conflicts, clashes of will or story tension, the ideas that lie behind a story’s themes cease to be merely abstract and become people actually doing things to each other or reacting to the action. As has been already explained, film dialogue is best when it has an immediate purpose and produces visible reactions in others. This is the essence of drama. Because character is not a static quality that belongs to a specific figure, rather than thinking of individual characters in the world it is far more useful for the writer to consider the notion of character-in-action-and-reaction. A story’s energy comes from the degree to which its characters are warring elements, complementary aspects that illuminate each other by contrast and conflict. The only practical reason for a particular character’s existence, in fact, is to interact with other characters.

—Alexander Mackendrick, On Film-Making

Necessary exceptions when mapping character relationships

Of course, as in real life, character relationships aren’t all identical or formulaic. That’s not how relationships work.

If you’re writing dynamic characters and a story with real change, there are some important exceptions you’ll need to consider.

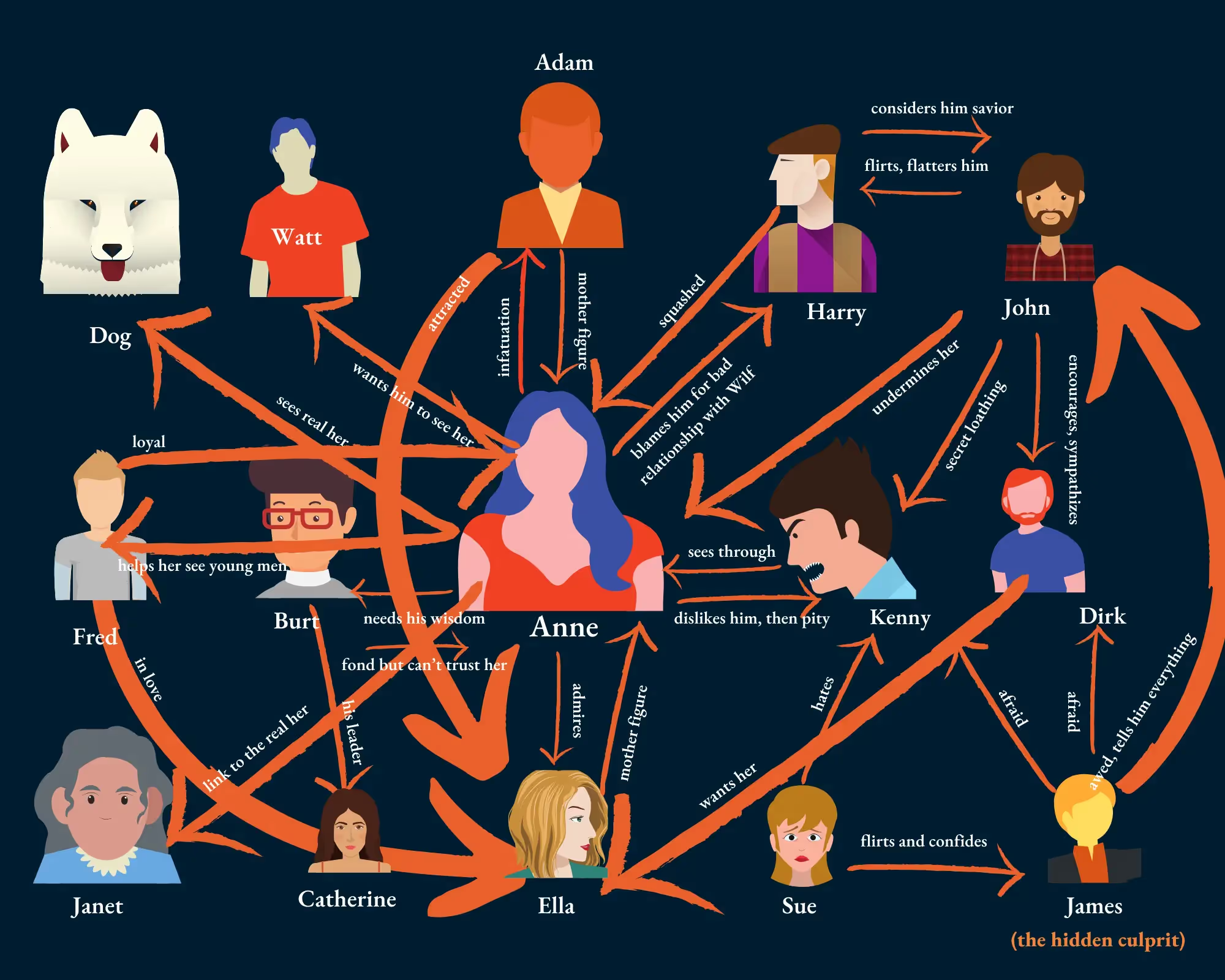

The culprit

Consider the ‘mute’ character who is present but seems to offer neither conflict nor assistance – a figure particularly useful if you’re writing a whodunnit.

This passive beast, appearing quite often in the story, without apparent agency, can be your secret agent, your ticking bomb.

Because they’re there, but don’t seem to be doing anything in terms of your story, your reader won’t be able to do the usual mathematics of story in which they’ve been trained since a child, and 2 + 2 won’t be coming up with 4. You’ve created a blind spot, a little piece of magic taking their eye off the ball. Nice one!

Create a network of character relationships

Once you’ve got your story up and running, you’ll be able to flesh out the network of character relationships. You can use this network to refine your storytelling in each and every scene by remembering what each character wants.

In any conversation or activity, they’re after their own fulfilment, acting with the same wholeness people do in real life.

This is tricky at the beginning of a first draft, when you’re writing a little bit to work these things out. But the sooner you start to sketch it out, the more integrity your story will have.

The comic element

In comedies, the joker of the pack has an absurd lack of requirements of others. Think Being There by Kozinski, or Forrest Gump, or Baldrick in Blackadder. They have a one-way relationship to others, which is lacking in complex wants and needs.

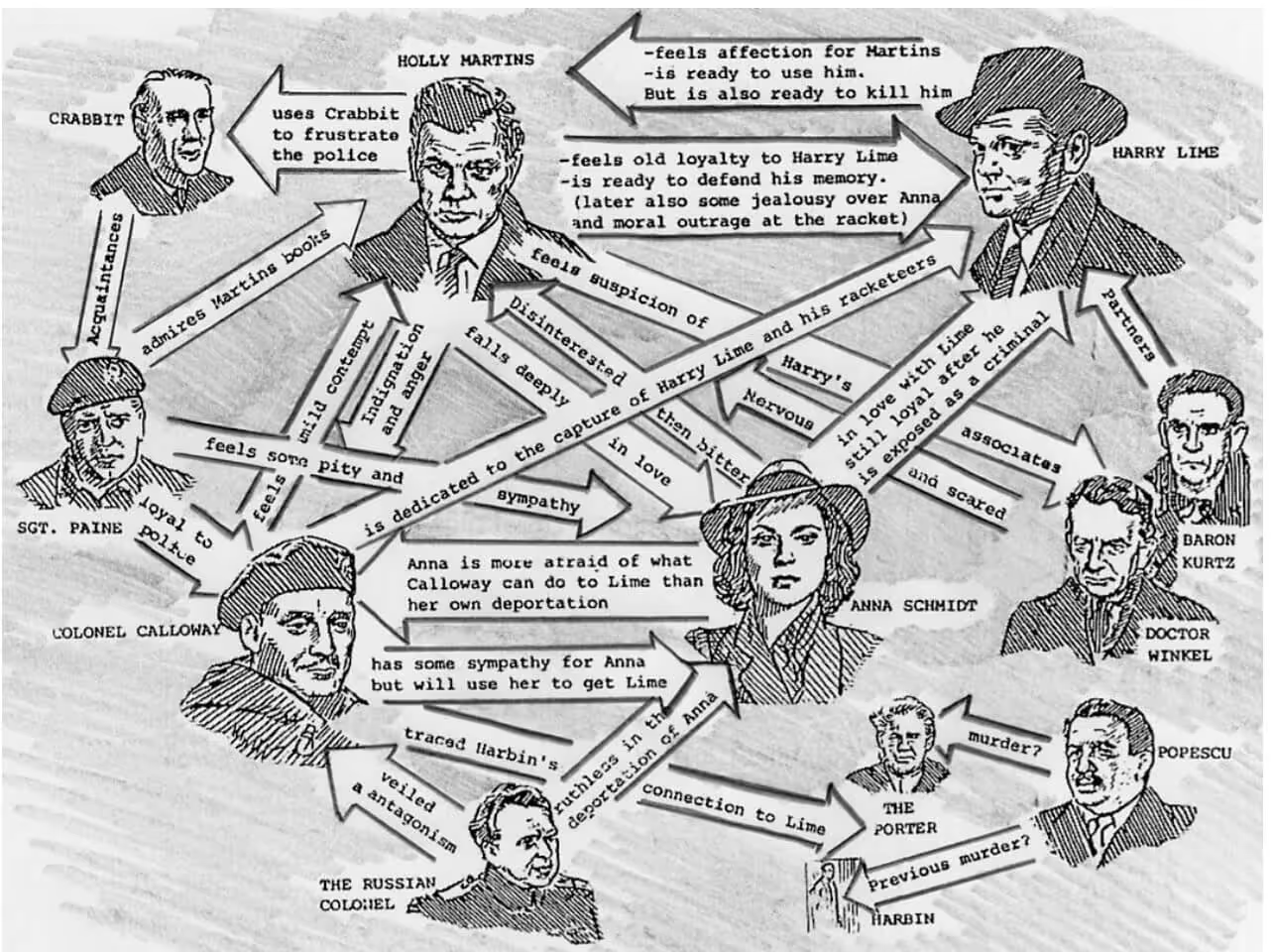

The network of relationships

Alexander Mackendrick’s wonderful book On Film-Making gives an example of Graham Greene at work on turning his short story into the movie The Third Man. (The article is attached as a download in the lesson pack for Character Mapping in our novel writing course. In that lesson, you will also find my own example of a network of active and believable character relationships, and how to prepare your own.)

Here’s the character map Mackendrick prepared for The Third Man.

Graham Greene’s description of the cast as individuals was wholly concerned with their relationships – what they want from each other – and not interested in physical descriptions whatsoever.

Interestingly, in my favourite Greene novels, the sentimental End of the Affair and The Heart of the Matter, God is a character with which Catherine and Scobie have very real relationships depicted by what they want from Him and He wants from them!

Try framing characters by their relationships in your own story

I rarely offer physical descriptions of my main players. It’s too trivialising and inimical to the purpose of this wonderful medium in which souls are almost unembodied, offering us an immersive experience of entertainment.

Instead, many good authors suggest their main characters’ appearances through how other characters feel about and respond to them. This is beautifully and knowingly handled by F. Scott Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby. Jay Gatsby means different things to different people, but Daisy is one character we know is beautiful because of the reactions she elicits. Daisy offers a masterclass in ‘being beautiful’ when she works hard to cause reaction by lowering her ‘low’ and ‘thrilling’ voice to make people come closer to hear her.

Start writing a novel today at The Novelry and enjoy the lesson pack on Day 5 to find out how to create your character network.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)