Do people keep telling you that you should write a book about your life?

Perhaps you’ve started a draft. Or perhaps you’ve read some great memoirs recently, and you want to write your own, but you’re not sure where to begin or how to move forward with the material you have. With the help of these five tips, you could be writing a first draft of your memoir over the next ninety days.

In this article, writing coach and award-winning author Alice Kuipers offers aspiring memoirists five of her best tips for writing memoirs. Alice is the author of a memoir for teenager Carley Allison, Always Smile, and a bestselling ghostwriter experienced in writing adult memoirs. She coaches YA, children’s fiction and memoir at The Novelry.

.avif)

How to write a memoir

The world of memoir writing is full of great storytelling and rich written material, and writing a memoir is a grand life adventure. For those of us who want to share personal essays and our lived experiences with others, the sheer complexity of our lives and the multitude of stories within can make the idea of beginning or finishing a memoir intimidating.

As memoir writers, it’s always helpful to understand the genre and the expectations a reader will have so you can start to structure and shape your unique narrative. Think of this as your first essential ingredient. After that, we have four other ingredients for a successful memoir so you know how to distill moments of your life to share them with a reader. Let’s get cooking!

.avif)

1. Defining memoir

You may be wondering whether the memoir form is the right way to tell your story and what exactly a memoir is. Often, aspiring writers are curious about three types of life-writing that can all become long-form manuscripts.

These three are autobiography, autofiction, and memoir, and knowing the differences between the three will help you understand what type of life-writing is most suitable for you.

Autobiography

An autobiography spans an entire life.

While some great autobiographies have been written by the author, like Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave by Frederick Douglass (1845), many are written by someone else, often after death.

Often, autobiographies are written about people who are famous or who have lived through extraordinary times. Sometimes they’re ghostwritten, meaning someone else writes the book but doesn’t have their name on the cover.

In an autobiography, a reader would expect to learn about the events of a full life—birth, education, key relationships, work and achievements, and so on.

Autofiction

Inspired by events from your own life, an autofiction is a novel that uses the facts of your life to get creative.

An example is Heartburn by Nora Ephron. In Heartburn, Ephron details the breakup of a marriage between Rachel, a food writer, and Mark, a political journalist. The marriage falls apart because Mark has an affair, just like Carl Bernstein, Nora Ephron’s real-life husband. Books like this are sometimes called narrative non-fiction, and often, the terms autofiction and narrative non-fiction are used interchangeably.

Our wonderful editor Sadé Omeje, who edited and acquired for HarperCollins, says:

Memoir and narrative non-fiction—what’s the difference?

Memoir as a genre can sometimes be difficult to initially differentiate from other non-fiction forms, such as narrative non-fiction. But narrative non-fiction, or what’s known as literary non-fiction, is a true story written in the style of fiction. The prose is compulsive but factual and strung together through the narrative literary techniques the writer adopts for their work.

Narrative non-fiction conveys real-life stories or events with a style of prose that reads like a novel.

—Sadé Omeje

Memoir

A great memoir shares an intimate portion of the author’s life with a reader, illuminating a truth.

What this means is that a memoir does not cover your entire life, nor all the adventures within, but only a period of your life—this can be a relief to a potentially brilliant memoir writer, taking away the worry that you’re supposed to write about everything that’s ever happened to you. (This is expected in autobiography, but not in memoir.)

The expectation from a memoir reader is that the memoir covers a period of time or an aspect of the author’s experiences, illuminating something about life.

Sadé Omeje explains:

Memoir is a first-person account of your own story, and emotional truth is often the basis for this genre.

—Sadé Omeje

There are many types of memoir, such as confessional, transformational, travel, profession-based (i.e., life as a treasure hunter), celebrity, grief, illness, etc.

Writing coach and bestselling author Evie Wyld says that:

The artist is what defines memoir for me. It’s impossible to tell the truth about something. You can only give a single point of view, highlighting the things you found important about the subject. I think it’s the artist’s intention that matters, the fact that they are trying to get to a certain truth about their own experience, and they choose to engage with the world through the medium of memoir—it invites a set of questions from the reader that perhaps fiction doesn’t in the same way.

—Evie Wyld

2. The question your memoir explores

When you open the pages of a great memoir, you uncover the question the memoir will answer for the reader.

While memoir is rooted in your life and what’s happened to you, a reader wants to read it because it answers something for them about the world. Example questions might be:

- Will love conquer all?

- Can one human survive when the world is against them?

- Can we navigate grief?

- Are secrets best left buried?

At The Novelry, we think of this as the question that pulls a reader through your book. Interestingly, as you start to think about what the reader is reading to find out, it helps you discover how to write your memoir.

.avif)

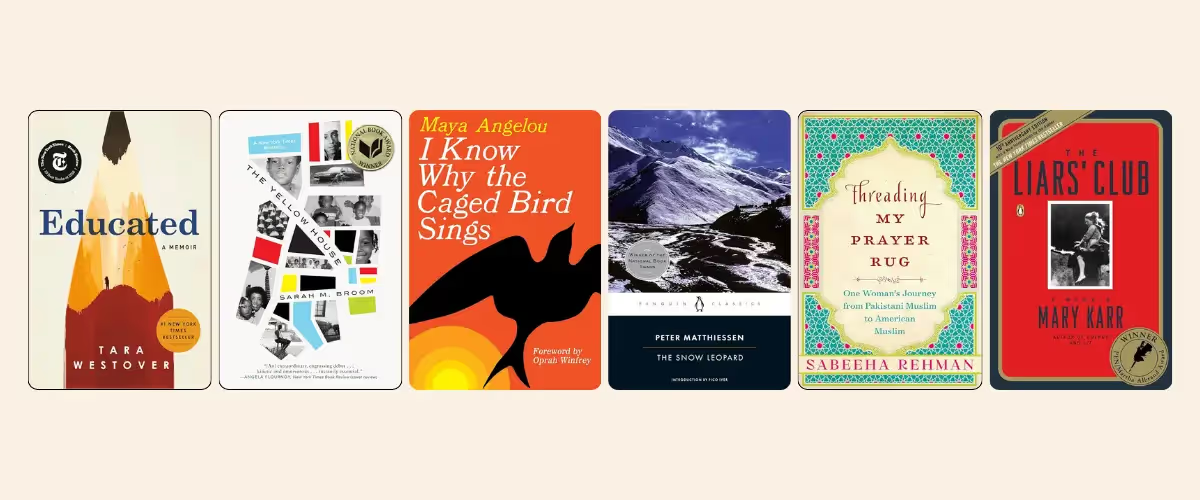

Examples of memoirs and the questions they ask

Educated by Tara Westover

Are grit and resilience enough for a woman raised by survivalists to truly live?

The Yellow House by Sarah M. Broom

What does home mean to you?

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

Can love for yourself and for words overcome terrible trauma?

The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen

While searching for something else, can you find yourself?

Threading My Prayer Rug by Sabeeha Rehman

What is interfaith understanding?

The Liars’ Club by Mary Karr

What happens when we expose family secrets?

As you think about your reader and look at how other memoirists have explored questions for their readers, it can help to do some exploratory writing. This is because the question we might be exploring for the reader is often a question we’re exploring for ourselves.

No matter whether you’re just starting to think about your memoir or you’re many pages (or drafts) through, try taking a few minutes to write about the bigger question your memoir might be asking. Doing this by writing is a great way to uncover deeper truths.

Ask yourself the following questions and write possible answers:

- What are you writing to find out?

- What might your reader be seeking by reading about your life?

- What are some things you know because of the life you’ve lived?

- What could a reader find out about the world from you?

.avif)

3. Structuring your life story

Now we know that memoir explores one question and covers a portion of our life, we start to choose which part of our life we want to work with. But how do we decide which scenes and moments to write? There are so many!

At this point, you have to start thinking like a storyteller, knowing that your story is important and that, while your memoir explores true events, structuring the story is the next key ingredient.

Story implies somehow that we’re making something up, but while we use the facts of our lives when we’re writing a memoir, when we uncover the structure and shape of the story, we shift toward creating a manuscript that a reader will connect to. That’s because human beings understand the shape of story—it’s in our DNA.

As Emily Esfahani Smith says in her TED Talk, There’s More to Life Than Being Happy:

Creating a narrative from the events of your life brings clarity. It helps you understand how you became you. But we don’t always realize that we’re the authors of our stories and can change the way we’re telling them. Your life isn’t just a list of events. You can edit, interpret and retell your story, even as you’re constrained by the facts.

—Emily Esfahani Smith

.webp)

The Five Fs in memoir

At The Novelry, we teach story structure using The Five Fs®, which refer to how a main character changes from the start to the end of your book. In memoir, the main character is YOU. As you find the shape of your memoir, you’ll see how the main character—YOU—has gone through a transformation and how important that is by using The Five Fs to look at that story arc.

Your character (you) will need to develop through your story structure, so a reader will discover who you were and how you changed.

In memoir, as in fiction, the first of The Five Fs is the Flaw. This is what makes life difficult for you at the start of your memoir—but you don’t (want to) see that yet. This is who you were before the events of your life changed you.

The remaining four stages of The Five Fs work through the typical pattern of a great story structure, and they can be applied to memoir just as they can in fiction, meaning that your book will finish with the main character—you—finding your place in the world. We delve into The Five Fs more deeply in our courses, with a specific Memoir Mini Course folded into The Ninety Day Novel Class.

It’s worth taking a moment to ask yourself if you can see your Flaw for the part of your life you’re thinking about writing clearly enough. Has enough time gone by for you to be able to write about this experience? Or do you need to write about something else for now?

Moving forward to the next ingredient, now you’ve started to think about structure, it’s time to start writing!

.avif)

4. Write first, edit later

Memoir writing can be a therapeutic and cathartic experience, but when you’re worried about how your storytelling impacts others, the very personal journey of writing the book can be inhibited. You stop writing for fear of hurting those you love.

At this stage of your writing, our advice is to try to write as if no one is watching. Later, you can pull out material you don’t want others to see, but for now, explore your story expansively. See where the writing takes you.

%20(2).avif)

It’s normal as a writer to want to share work and find readers, but putting your personal story out there is bold and frightening. It can also be triggering and traumatic. The fear of sharing work with the world can stop many memoir writers from beginning. You’re worried about what your family will think when they see what you’ve secretly been up to, and this doubt and fear can halt your writing progress.

Memoirist Alice Carrière uses this doubt and fear to dig more deeply into the work:

The process of doubting is just the process of living for me. And I think it was precisely that doubt that not only splintered and shattered me but also gave me the capacity to connect in a way that I never thought possible. It gave me the opportunity to listen to my father’s story, to humanize my mother in a way that I don’t think she ever could and to recognize the humanity in myself even when I couldn’t recognize my own face in the mirror.

—Alice Carrière

Many writers worry about what is legal and what permission they may need as they consider the big dark secrets a family may not want to be shared, and how those are perhaps going to be received out in the world. It’s reassuring at this stage to remind ourselves that we can ask for permission before we publish, later on, and we can also change words, delete, remove, and edit out sections of material that we don’t want to share. But we have to write a draft first.

Explore what is possible on the page before you censor yourself. For now, you’re writing to see what the book could be, and a useful reminder is that your first draft won’t be the last.

.webp)

Practice freewriting

One technique you may enjoy is freewriting. Freewriting asks you to write without stopping. Don’t go back over, delete, or fix. Let the words flow for now. Try writing to a time window—ten minutes, say.

When you brave this type of writing, you’ll be exploring what’s possible on the page, but not pressuring yourself to write perfectly or even in a way that makes sense: this fits well with memory and allows the memories to surface, helping you catch those glimmers. The hand you held when you walked in the puddles with your wellington boots on. The table you played under as a child while you overheard people shouting at each other. The toast crumbs on your lips when your father told you bad news.

This writing process opens up the possibility of a finished written idea.

It can be utterly intimidating to ‘just write,’ but if you learn to let go and get words down onto the page, trust us that it can help you reconnect with your lived experiences.

As you write quickly, the light you shine upon the memory glows and you remember more. The glimmers grow. Details come. Moments of long-forgotten dialogue. The way the sun felt on your skin...

{{blog-banner-11="/blog-banners"}}

5. Research techniques

As you write your memoir, you’ll be writing about places that possibly no longer exist, using memories that may not be vivid.

Figuring out how to explore the past is one of the challenges and joys of writing memoir, and many memoirists find the research leads them to new ways of looking at the story.

Some places memoirists research include:

- photo albums

- diaries

- newspaper articles

- the internet

- interviews

- archives

- physical objects

- in-person visits to places

- ephemera

Among the diaries, articles, photo albums, physical objects, ephemera, interview transcripts and more, it’s important to stay organized, make notes, and balance the lure of doing more research with actually writing.

Writing coach Heather Webb says:

I do a bit of ‘front loading’ in which I spend four to six intense weeks doing nothing but reading and organizing my research. From there, I work on a synopsis, pitch, and character sketches. Once I can picture the opening scene in my mind, writing begins! My rule of thumb with rabbit-holes is this: while drafting, I’m only allowed to stop and research if it will prevent me from moving forward with the plot. If it’s more detail-oriented research that’s related to world-building only, I use parentheses to document what I need to look up later, and then I keep writing. During my second draft, I will stop to research in dribs and drabs to fill in those parentheses. This prevents me from spending too much time on information that isn’t essential. I’ve learned this the hard way!

—Heather Webb

.avif)

As you begin your research process, look at the list above and select what research you might need and want to do, and how long you want to spend on it.

- Who could you interview?

- Where could you uncover information?

- Who might have photos, birth certificates, family trees or other ephemera?

- Which places might help you remember?

Tara Conklin, one of our writing coaches and a multi-published author, describes how Alice Carrière roots her writing in place in her memoir Everything, Nothing, Someone.

She writes about the journey to forgive her parents for their deeply flawed parenting. She begins the story of this journey in her enormous and chaotic childhood home where she lived with her mother—a home that serves as a kind of metaphor for the author’s childhood itself. She ends with her mother’s death inside that same house. Place is defined early on as an important element in Alice’s journey. Each location is described in detail—her father’s home in Paris, Alice’s studio apartment in New York, the sprawling residential mental health facility where she is treated—and the arrival and departure from each of these places act as important markers in Alice’s journey.

—Tara Conklin

When you’ve uncovered whatever it is you’re going to work with, take a little time with what it meant to you before you begin. Sit somewhere quiet and see what the memories are.

Not only are you gathering concrete facts and details as you do your research, but you’re also using this as a way to uncover parts of your life that you perhaps had forgotten or remembered differently.

.avif)

Interviews

Talking to people from your past can be illuminating, but it can also bring up a lot of other emotions when you’re writing memoir.

Prepare your questions first, but be open to a semi-structured shape to the conversation. What we mean by this is that, as the conversation unspools, check your questions, but don’t force them in the original order if the natural shape of the memories and experiences go a different way.

Be wary if you’re getting defensive. Your role as interviewer is to listen and gently prompt and probe. You do not have to like what you hear, and you may wish to respond, but you can save your responses for a follow-up conversation if one is needed, once you’ve had time to process someone else’s interpretation of events.

Interview only in the quietest of places. A cafe has far too much background noise, for example, and can eradicate your most intimate and valuable moments with the clatter of crockery.

If it’s safe and quiet, interview the person in their home. This makes them most comfortable and gives you room to get a stronger sense of who they are—their character is revealed by their setting—and the objects in their home may spark memories of your own past, depending on who they are to you.

Be kind to yourself throughout the memoir writing process

As you’re researching and thinking, you are perhaps facing some painful experiences.

It’s vital that you care for yourself during the whole writing process.

Yes, it’s possible that writing memoir can be cathartic and therapeutic, but often it can also be exhausting and distressing, too. As author Koren Zailckas says:

I don’t know where the idea originated that memoir writing is cathartic. For me, it’s always felt like playing my own neurosurgeon, sans anesthesia. As a memoirist, you have to crack your head open and examine every uncomfortable thing in there.

—Koren Zailckas

Ultimately, writing a memoir is about making connections and uncovering the story within.

Melanie Conklin, author and writing coach at The Novelry, says of writing about her life:

When I drafted a middle-grade memoir in graphic novel format, I found that exploring my own life as a narrative uncovered threads of connection that I was previously unaware of—even parts of my life I thought I knew well! The narrative lens allowed me a certain emotional distance to examine the patterns before me, as well as tools to dive deep for new connections I hadn’t previously made.

There were moments when I felt as though I was unearthing my own story. It reminded me of Stephen King’s advice in On Writing, where he describes the telling of a story as an archaeological excavation. Telling a story from real life is no different. There is still a narrative structure to create so the reader is propelled through the events in a way that is both meaningful and exhilarating.

Seeing my own life from that generous viewpoint unlocked new pride and compassion for myself as a young person and the struggles I faced. Delineating my own path to success affirmed who I am as a person. That is the power of narrative memoir.

—Melanie Conklin

When you use these five ingredients for writing a memoir, you’ll find your work is stronger and your motivation is more focused. You’ll discover connections you hadn’t seen before, deepening your structure and helping a reader discover what it is that you know about the world because of your unique life story.

Memoir writers can find a home at The Novelry

Join The Novelry and learn from our Memoir Mini Course, with even more thoughtful guidance and advice from award-winning author Alice Kuipers.

Welcome home, writers. Join us on the world’s best creative writing courses to create, write and complete your book. Sign up and start today.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)