If you are writing a crime fiction novel, you may be concerned about how much accuracy readers expect from the genre. Do you need to be undertaking hours upon hours of dedicated research time to ensure complete and faithful accuracy to reality?

Sigh a breath of relief, crime fiction writers: the answer might offer a lot more leniency than you’d expect.

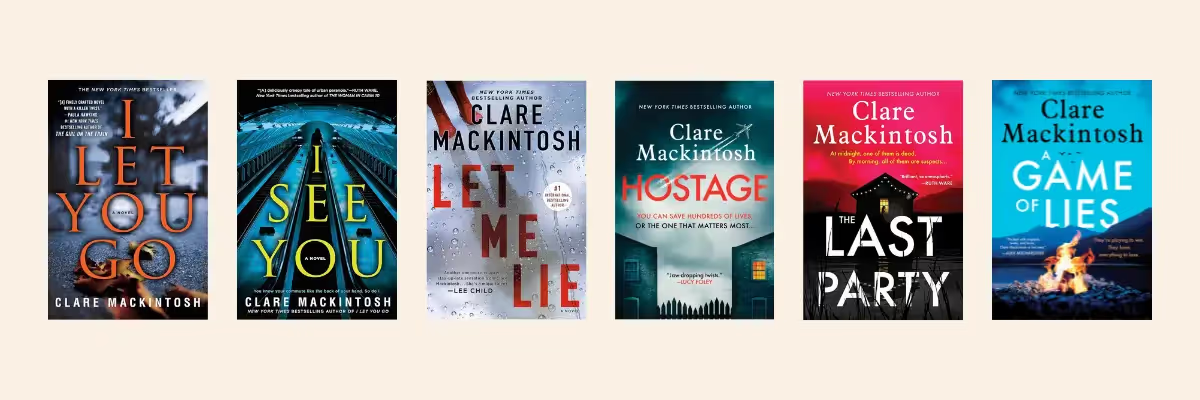

In this article, bestselling crime fiction author and The Novelry writing coach Clare Mackintosh examines the elements of crime fiction that usually demand accuracy, including rank structures and job requirements, the role of technology in every process, and the average timescales of police procedurals. With real-world experience in crime scenes, Clare Mackintosh is the multi-award-winning author of seven Sunday Times bestselling novels, including the New York Times bestseller I Let You Go, which won Theakston’s Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year, Best International Novel at the Cognac Festival Prix du Polar Awards, and was the fastest-selling debut crime novel in its release year. At The Novelry, Clare coaches crime and suspense, memoir, and psychological thriller.

Ultimately, Clare demonstrates that while it’s important to remain faithful to reality when writing crime fiction, striving for complete accuracy might become more of a hindrance than a help—especially if it prevents you from writing.

Advice from Clare Mackintosh, former police inspector and crime fiction novelist

As novelists, we enter into an unwritten contract with our readers the second they pick up one of our books. I do solemnly promise to open a portal to a world so real you will believe you are truly there.

The reader trusts the author to be a safe pair of hands as they follow us across the threshold. This pressure for realism can be daunting for emerging crime and thriller writers, in particular, who generally don’t have firsthand experience of solving murders (or committing them, one hopes).

But how important is accuracy in crime fiction? I put it to you, Your Honor, that it’s a lot less than you think.

For over a decade before I became a published author, I was a police officer. I worked on murders, serious assaults, and robberies, then later specialized as a public order commander. When it comes to crime, I know what I’m talking about, and my debut novel, I Let You Go, was as procedurally accurate as I could make it. Ten years (and several more crime novels) later, however, my approach to accuracy has become significantly more fluid. In this article, I’ll explain why.

Mistakes happen in writing

It is almost inevitable a writer will make mistakes. We don’t always ‘write what we know,’ and even extensive research is likely to make us armchair experts rather than hands-on practitioners.

I spent hours with a Boeing 747 pilot when I was writing my airplane thriller Hostage, but trust me, you don’t want me landing your plane. Whenever I doubted myself as a ‘safe pair of hands,’ I reminded myself that on a Venn diagram of readers, the intersection between ‘people reading my book’ and ‘people who know how to fly a plane’ would be very small, and the proportion of those who would notice or mind a small error was so much smaller as to be insignificant.

None of us wants to write something wildly incorrect, but don’t beat yourself up about something minor. It happens to the best of us. (Sidenote: praise be to copy editors!)

The reader wants a hero

A real-life incident room—the type set up to solve a murder—could have 30 or 40 people working in it. Actions are distributed according to skill and seniority, but also according to availability, and a seemingly straightforward task could turn up an important clue.

Replicating this degree of accuracy in crime fiction would be disastrous. Readers don’t want to meet dozens of characters; they want to follow one or two hero detectives, the good guys, plus a small supporting cast. That crucial lead that tips your story into act two needs to be uncovered by your heroes, not by an officer they’ve never met before who happened to be allocated the task on HOLMES.

As a young detective seconded from CID to Major Crime, I was given a list of phone numbers to call. It was a tick-box task, created for completeness and without expectation. However, one of those numbers resulted in my flying to the States to interview a significant witness who refused to speak to anyone but me—much to the chagrin of the permanent and much more senior members of the team!

In a real-life incident room, a breakthrough can come from anywhere, but in a novel, it needs to come from a character in whom your readers are invested. Create realism by giving an impression of teamwork while reserving for your protagonists the main-character energy they deserve and readers expect.

A detective with a one-track mind

Most homicide detectives carry a heavy caseload at any one time. Some of these jobs will be active investigations, some might be awaiting trial, others pending filing. All will require constant work; the equivalent of spinning plates, albeit some spinning faster than others.

Do we need this level of accuracy in a crime novel if there are no links between the investigations?

We don’t, and it can be confusing for the reader and may take the focus away from the protagonist’s quest. Instead, as above, create the impression of a heavy caseload, but keep the camera pointed at your primary investigation.

Computers solve crimes...

...but in a fictional world, we like humans to do the work.

There’s a lot of nostalgia around old-fashioned policing, but things have moved on since Morse’s day, and the fact of the matter is that a lot of investigative work takes place at a desk. Writing or reading statements, preparing court files, watching CCTV footage, looking for open-source intelligence...

Although some of this will be reserved for civilian case workers or specialist departments, your ‘OIC’ (officer-in-the-case) is likely to be staring down the barrel of a screen for several hours a day. But you don’t need to write it that way: accuracy should never be at the expense of story.

Accuracy should never be at the expense of story.

—Clare Mackintosh

Office-based scenes can be great for showing the dynamics between characters, but make them brief: keep people moving. The drive for efficiency means your OIC could probably confirm something with a witness via text or email, but wouldn’t it be better for them to knock on the witness’s door and hang out in their kitchen for a while? Who knows what they might discover while they’re there?

The seduction of rank in police forces

Like most organizations, police forces are pyramid-shaped.

At the top are the small number of senior managers wheeled out to the public on special occasions, and at the bottom, you’ll find the many (although never enough) officers on the front line.

It is these front-line officers—the uniformed police constables, the plain-clothed detective constables—who are doing the bulk of the work in catching the bad guys, but that is rarely reflected in crime fiction because readers have an unconscious bias toward seniority.

To be blunt, rank is sexy.

So, we have a Detective Chief Inspector taking a witness statement in person instead of sending a minion so she can finish her end-of-year appraisals. This isn’t necessarily true to life (although some senior officers are more hands-on than others), but I say go with it.

Sometimes, tropes create reader expectations, which become so embedded that the real picture would be a disappointment. (As an aside, there are advantages to using rank in fiction: senior officers are less answerable to management, which can inject a little more flexibility into your storyline.)

{{blog-banner-13="/blog-banners"}}

Bending time in police procedurals

I once waited seven months for a forensic sample in a fraud case to come back from the lab, by which time the offender had skipped the country and was never seen again. Forensic turnarounds are famously slow, and although that can sometimes be a gift for a plot, nine times out of ten, we’re going to need a result sooner in order to maintain the pace of the story.

I make no apologies to my former colleagues for the same-day results DC Ffion Morgan procures by bribing CSI with cookies. I know that’s not how it works (although don’t tell me you wouldn’t be at least a little bit swayed by a chocolate chip cookie...), but the plot demanded it.

Readers won’t sit around waiting for a DNA sample to get to the front of the queue, especially in the final stages of a crime novel when the clock is ticking and the tension’s high. Most delays in an investigation are due to the volume of work waiting to be processed, and a job can be bumped up the priority list if there’s enough pressure from the top.

That’s not always possible in real life, but your fictional overtime budget can flex to suit your plot. Have your detectives frustrated by a shortage of resources for a midnight murder scene, or roll out the CSI circus at three in the morning. It’s your call.

Truth isn’t always stranger than fiction

Sometimes, you come across a crime so extraordinary no reader would ever find it plausible, but such crimes are rarer than you might imagine.

In my experience, the majority of crimes aren’t nearly exciting enough to form the basis of a thriller. They’re solved right away, or they’re never solved at all—neither of which lends themselves to a satisfying narrative arc.

Similarly, on-screen and on the page, we love a Machiavellian arch-nemesis, but the common-or-garden criminal is rarely as clever. I’m reminded of the serial burglar who broke into a house the day after I’d released him from custody. ‘How did you know it was me?’ he asked me when I arrested him, whereupon I showed him the bail sheet with his address on it, which he’d dropped at the scene of his crime.

As it happens, my debut novel was inspired by a true crime—a hit-and-run on the outskirts of Oxford—but the key word here is inspired. Use true crime as a departure point for your own fictionalized crime. I guarantee you’ll come up with something far more gripping than reality.

Research isn’t writing

When you’ve spent a great deal of time finding out how something is done (and despite my enthusiasm for artistic license, there will be elements of your story you do need to get right), it is tempting to tell the reader everything.

The weight of a side-handled baton, the precise chemical makeup of CS spray—trust me, the reader doesn’t need to know it, and a surfeit of detail risks slowing the pace of your novel.

What the reader needs to know is how your protagonist feels with that baton in their hand; and how the villain reacts to a well-aimed spray of gas in their eyes.

Sometimes, the research you do will threaten to derail your entire novel. There is no worse feeling, but when this happens, take a deep breath. There will be a way around it. My personal approach to research is to use the results to inform my stories, not to create them. Like grammar, I want to know the rules, but I don’t necessarily want to follow them. Whenever I’m forced to deviate significantly from reality, I often have a character acknowledge the unusual circumstances. It’s most unorthodox, but...

Finally, in common with many writers, the author’s note at the back of my books always includes a disclaimer. All mistakes are mine and made for the purposes of the plot. I think that covers a multitude of sins, wouldn’t you agree?

.avif)

So, how important is accuracy in crime fiction?

It is, of course, your novel—so the answer is that a crime novel should be as accurate as you’d like it to be.

But I come to you as the author of eight mystery and thriller novels that have collectively sold more than two million copies and as a former police officer who gives you her blessing to bend the truth for the purposes of a good story. You are writing a novel, not a police training manual, after all.

The author Sophie Hannah, who in addition to her own brilliant psychological suspense novels has written several Poirot books for the Agatha Christie estate, says that she never asks herself whether something is probable, but only whether it is possible. If it is, she will run with it. It is excellent advice, and I would add that I think we crime writers should strive not for accuracy but for authenticity.

Watch fly-on-the-wall documentaries and make notes on how police officers talk; note the difference in speech patterns when they’re talking to members of the public versus their colleagues. Follow them on social media to get a sense of their caseloads and the pressures they face. Inhabit your characters as they transition from home to work and back again. How do they feel? What are they thinking? What are they scared of? These are the things that will bring your story to life.

In short, don’t lose sleep over how accurate your crime novel should be. Don’t get it right; get it written.

Welcome home, writers. Join us on the world’s best creative writing courses to create, write, and complete your book. Sign up and start today.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)