1. Set up a good story

Your first idea for your story most likely won’t be ‘the one.’ Ideas start out shabby, and we work at them to make them better, seeing something in them that sparked the idea and giving it a little encouragement to grow.

Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple and learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen.

—John Steinbeck

Once you permit yourself to have shabby ideas, you’ll find you get a whole lot more. When it comes to creativity, neither economic theory nor the scarcity principle applies! There is more supply when there is more demand.

You’re going to have a bunch of ideas once you open the door to the possibility of having a story to tell.

Plus, you’re going to open your mind to a new life. That’s not as woo-woo as it sounds. In fact, you’re going to open a door to living many new lives in this lifetime of yours. Fiction imagines the lives of others, and both author and reader walk them. (Time to drop the ‘YOLO’ bumper sticker!)

Many writers report a very common dream type when they’re writing. It’s the dream of being in a familiar house and discovering rooms behind staircases you never investigated. In the dream, you think to yourself, Wow, this was here all the time, why didn’t I explore it before now?

If you’re someone who’s into property porn, you just love browsing those real-estate websites, then it could be you’re craving a whole new chapter of life. You can satisfy that craving more affordably with a manuscript than a mortgage!

Don’t wait for ideas to come to you. Go out and about with a net. Do things differently. An author has a faculty for making use of whatever presents itself. Go to the supermarket, get on a train, eavesdrop, and consider strangers in new ways. Ask yourself questions about these people.

What if, when they got home, they found...?

What little thing is keeping them distracted right now from something major that’s about to happen?

Listen to people at work, in meetings, at events. Do more listening than talking and think to yourself—what one thing might unsettle this person’s life entirely? That’s a story.

If you’ve written before, or you’re aiming to get published this time and you mean business, consider a technique we share in our Advanced Outline Class. Start with the endgame. In publishing, ‘comps’ or comparison titles are used to sell books to agents, publishers, and bookstores. Typically, there are two to give the new idea dimension. One is usually a market-leading title from the last 3–5 years. One is there for storyline, the other for genre or treatment. But my tip is to add a third at the early stages of ideation. Add a wildcard for pure magic, something with great energy or emotional meaning to you. So, for example, you might look at the bestseller list at The New York Times this week for one title, then add another, and a third might be an off-the-wall title you adore, your secret weapon, if you like, which you’ll never reveal, but it brings the magic.

Here’s an example:

The Wedding People by Alison Espinach (storyline), The Slap by Christos Tsiolkas (episodic treatment), and Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut for sheer magic of voice, speculative possibilities, and tenderness.

Choosing a very plain and straightforward title sooner rather than later helps you stay on track as you start writing and stick to the brief. Remember, the title encapsulates the agent of change in the story, the genie that changes everything for your main character.

Remember, story ideas don’t come fully formed. It’s not like swiping left or right on Tinder. Writing a book is a relationship.

Writing a book is an adventure. To begin with it is a toy and an amusement. Then it becomes a mistress, then it becomes a master, then it becomes a tyrant. The last phase is that just as you are about to be reconciled to your servitude, you kill the monster and fling him to the public.

—Winston Churchill

2. Don’t worry too much about being a good writer

The opening line

Be playful with the first line, but tell yourself this won’t be THE first line. Some of us have been known to ‘write backwards,’ adding new material to what happened before we started the story as the setup and prior events take precedence.

You won’t nail it when you put your fingertips to the keyboard for the first time. Tell yourself, this won’t be the first sentence. It will go. Knowing that takes away the stage fright. Your first sentence might lie hidden in the first chapter, and you’ll only find it later. Let it lurk. It will rise to the top as you delve further into the story. When you begin writing your story, simply make yourself at home in this first draft.

Consider making the opening line a pivotal moment. It can be trivial, but it should be pivotal, and tell us things are changing here, because stories are all about change. No change, no story. So the first line can be the first of many dominoes about to fall, and in its humble way, it is therefore momentous.

My own personal favorite is this from Commonwealth by Ann Patchett:

The christening party took a turn when Albert Cousins arrived with gin.

—Ann Patchett, Commonwealth

It doesn’t try too hard, but you get the sense this small thing will set events in motion. Note the voice too—so understated. We know we are in the safe hands of a storyteller.

You can see some great first sentences at our blog here.

For a long-form novel, the first sentence needs ‘legs,’ quite literally, in many ways. A novel is driven by the changing circumstances of one human being, and the changing moral outlook of that main character. It can be rooted in a fundamental misconception that’s going to shift during the course of the story, or a lie the main character tells themself.

Think of beginning to write a book as self-soothing.

It’s all self-soothing, really, until you get to second draft. Readers appreciate what we call in The Classic Storytelling Class ’a cozy start.’ Put us in this world and make us feel you are a safe pair of hands. Establish the world, the eyes, the outlook, the voice. Simply show us what you see. Again, don’t try too hard. Bring us safely and credibly to another place and make us feel at home in the first pages. Remember—we need to care.

Once you get to a second draft, you can be tougher on the work, and you should be. The job of each sentence is to get the reader to want to read the next one.

Compare your writing line by line once you have a setup you like. Be tough. Why isn’t yours as good, word by word? You know words can be changed, right? They’re not stones, rocks to haul around, they’re erasable.

If not as good, why not? If not, why not? This is how you learn your craft. If a word next to a word doesn’t seem important to you or to change anything, keep practicing. The first law of ambition that leads to achievement is to make things harder.

To make fiction come to life and feel true to the reader, use a real voice, not a ‘literary’ or writerly voice. Fiction requires authentic reporting. It doesn’t require original ideas, it requires true-telling. Real-life reporting creates reader immersion.

Test your words. Read it aloud. There is a line between using real reporting and storytelling. Go too far one way and it’s boring, no story (no change implicit). Too far the other and it’s a tired charade. Work between nature and art-ifice. You need the latter for drama, but not so much as to induce disbelief and prevent engagement.

Your job is to move between that unaffected voice and storytelling mode without sacrificing one to the other. This is the art of writing and the essence of its form of entertainment. All art is humanity’s attempt to improve upon nature. Entertainment compresses time and events to create sensation.

A technique to achieve this is a wry or humorous tone of voice that is ever-so-slightly removed but dry and measured. Once you establish that detached voice, it will guide you on how to unfold every sentence thereafter.

3. Don’t be a bad writer

This part is easy. Avoid the ham and cheese.

Ornate, baroque, and purple prose ruins stories. These words are used to elicit emotion, often where it is as yet unmerited in the development of the story and our immersion in it. That’s why you need a cozy start. If we don’t know the people in the story, we won’t care about them gurning, ‘gasping for air,’ and grasping at life in your first sentences. We will just grimace at the hamfistedness of the writing.

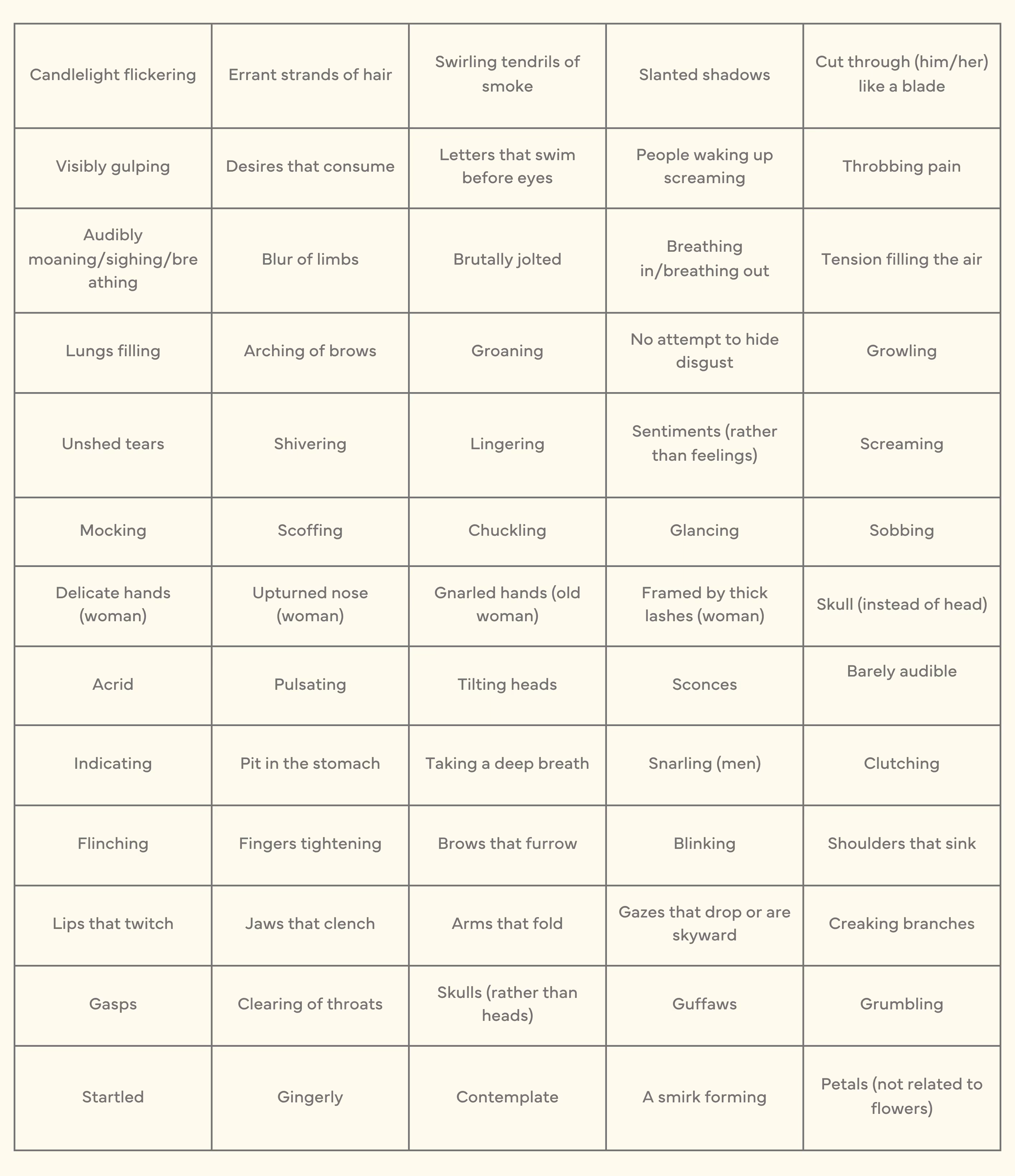

Two things: learn to skip what’s stale and dodge a fail.

Skip what’s stale

If we have seen it before, drop it on the floor.

Don’t use phrases or commonplaces we have seen before. Secondhand emotion is spent emotion. It’s already blown its load, and all the feels have been felt.

If you have seen two or more words hanging together this way before, choose not to reheat the stale mac and cheese one more time. When you see a hackneyed pair (an awkward silence, a mindless brute, the usual suspects, a pregnant pause), with adverbs often the clue to the sin (profitably engaged, readily adopted, precociously talented) and very often redundant ‘physically,’ ‘frantically,’ even ‘quickly.’

Play this track to prevent yourself from leaving them in situ.

Dodge a fail

This one’s easy. Leave out the dead words. Conventions make it conventional.

With the overuse of these words, you’re going into characterizations, stereotyping, and pastiche, and losing your reader. By using them, you cheat your reader of a firsthand ‘lived’ experience. Earn the right to our attention with unadulterated ingredients. Simply say what you see.

When we open your document and start reading, we, agents, and publishers give you an imaginary credit, and all you can do is lose points. The game is to keep your credit.

Here’s a game. Give yourself 20 points for even daring to write. Hoorah! Now deduct one for every single use of any of these words.

How many did you score? Delete, delete and raise your game!

It’s not that one of these words, singly, is bad. It’s that one seems to open a gateway to more and a pile-on of ornamental schmaltz.

{{blog-banner-4="/blog-banners"}}

Some final tips on taste and judgment

- Try not to begin with chests heaving, a person struggling to breathe, or a person waking from a bad dream.

- Don’t start with the main character dying (we don’t care).

- Don’t follow the common path of going from bad weather to a dead body.

- Forget the cloud formations and dust motes.

- Set aside everything you admit is ordinary, dull, boring. Maybe start after that.

- Dropping the word ‘fuck’ in the first pages doesn’t make this contemporary, or hard-boiled. (It seems to be mandatory for rookie writers.)

- Lose redundancies like a ‘silent head shake,’ a ‘low whisper,’ a ‘gentle nudge,’ an ‘unblinking stare,’ a ‘terrible mistake,’ ‘blindingly obvious,’ an ‘extraordinary coincidence.’ Don’t use two words when one will do. Don’t tell us about mouths that open but no words come out of them. A good writer doesn’t waste their words.

- A little kindness is a nice touch; not everyone has to be burnt out in fiction.

- The first three pages is too soon for grand aphorisms, or final or cynical statements on life.

- Don’t have characters speak with ass-hat rhetorical grandiloquence to each other, for example, ‘blah by blah, my friend, blah blah blah’ or bring old-world words into contemporary pieces, addressing each other as ‘dear’ or referring to a woman as ‘the lady.’ Keep it real.

Please read books. If you read books published now, you will see they just don’t do the things you think they do.

Sometimes, purple prose happens at a first draft, as we work our way into the story, when we don’t have enough cast yet or a problem in motion. This leads to a singular, sorry-headed cast member, the main character, wailing. What we want are events. Things must happen. If you haven’t got your cast or storyline (problem in motion) then you will be tempted to fill pages to find them. That’s fine, but it’s not ready for you to share with the world. It’s too soon. Fill the pages, by all means, but don’t waste a reader’s time with them.

When you do have a story, a problem in motion, and a cast, you won’t dither with the adverbs and adjectives. You will want to use every word wisely, with so much unfolding on the page!

Finally, the good news is that you are probably worrying about the wrong things. Don’t worry about grammar, punctuation, spelling, vocabulary, and so on. When the story is there, it simply unfolds. A writer has to learn to get out of their own way and let the story have its head. That learning process is often called ‘drafting.’

Onward! To second draft!

The winner of The Next Big Story

The Next Big Story prize was launched on May 1, 2025, with the mission to find a new voice in fiction and kickstart the career of a writer who might otherwise never have dared to put pen to paper. With a grand prize of $100,000 (£75,000 in the U.K.), our aim at The Novelry was to reverse the usual risk/reward scenario for writers and nudge people to get just three pages down to start their story.

It worked! The Next Big Story became the world’s largest writing prize with over 22,500 entries. The team at The Novelry worked around the clock to select a longlist and a shortlist before our panel of esteemed judges, chaired by Women’s Prize for Fiction winner Tayari Jones and guided by the public vote, chose the winner from our outstanding final eight.

You can find out who scooped The Next Big Story prize in 2025 right here.

Writing fiction brings a little bit of magic and mischief to our everyday lives, and writers become authors by turning up to the page, day by day. To those who entered The Next Big Story 2025, we salute you! To those who voted, thank you for reading. To our team and the panel of judges who read, read, and read again the entries, we thank you for being part of making a few dreams come true.

Wherever you are on your writing journey, we can offer the complete pathway from coming up with an idea through to ‘The End.’ With personal coaching, live classes, and step-by-step self-paced lessons to inspire you daily, we’ll help you complete your book with our unique one-hour-a-day method. Learn from bestselling authors and publishing editors to live—and love—the writing life. Sign up and start today. The Novelry is the famous fiction writing school that is open to all!

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)