Although Halloween is traditionally the peak of the spooky season, we sometimes find ourselves thinking about ghosts, gothic literature, and the supernatural at other times of the year. A pitch-black, snow-silent night in winter can be just as unsettling as a deserted sun-baked street in the height of summer, suddenly devoid of the shouts of children playing and the blaring of backyard music. The natural world—and the unnatural, unknown world—can scare a reader at any time in a well-written spooky story.

So, how can we write the type of fiction that sends shivers down a haunted reader’s spine and strikes fear into their heart? After all, inspiring a reader’s imagination to make them feel terror using only words on the page is the dream for any writer.

Anna Mazzola is here to help with eleven top tips on writing a story to chill the nerves. In this article, Anna looks at using ghostly tropes in new and exciting ways and how we can cast characters like those from the spookiest of classics by casting them in a light that today’s readers can relate to. Anna is the award-winning author of three historical crime novels, and her debut, The Unseeing, was awarded an Edgar Allan Poe award. Her forthcoming book is a haunting ghost story set in Fascist Italy.

If you’re looking to compose your own ghost story in a writing style that will leave any reader scared to turn the light off, read on...

Ten tips for writing spooky fiction and ghostly tales

Humans have always loved a good ghost story. Evil spirits and monsters formed the basis of many tales in folklore and mythology, far before such things as horror came to the fore and ghosts wafted about the works of Homer and Shakespeare.

The gothic novel seeped onto the page in the eighteenth century, with poor Conrad being crushed to death by a gigantic helmet at the Castle of Otranto in Horace Walpole’s eponymous novel. From then on, a growing army of ghost nuns, werewolves, and vampires would be employed to satiate the demands of the reading public hungry for a cracking ghost story.

In fact, the eighteenth century bred many great examples of unnerving literature, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which used the explained supernatural to explore the darker side of the human mind, to the clanking chains of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol and the creepy tales Henry James was spinning at the end of the Victorian era—and, of course, we must thank Bram Stoker for the undying influence of Dracula. Plus, gothic romance gave us the immortal Byronic hero, which even modern romcoms continue to cast!

Why do we love a good ghost story, gothic literature, and supernatural stories?

Many principles have become part and parcel of all that we consider creepy in creative writing, with stories of ghosts and haunted houses creeping into every aspect of pop culture, from the stories our parents told us weren’t real to innovative music videos and frightening Instagram filters. In fact, in the realm of the gothic, there are multiple subgenres, including Southern gothic, Russian gothic, and American Gothic. Not to mention the reams of romantic literature that draw on supernatural conventions, often now crossing over with significant areas of the romantasy genre.

And the scary ghost story is still going strong. Indeed, they seem to bloom like corpse lilies in times of trouble. As Stephen King says:

We make up horrors to help us cope with the real ones. With the endless inventiveness of humankind, we grasp the very elements which are so divisive and destructive and try to turn them into tools—to dismantle themselves.

—Stephen King, Danse Macabre

There is clearly an appetite for terror, the uncanny, and a good old ghost story, but how do you write something a reader will not forget—especially when they’re walking up the stairs to bed at night?

I don’t pretend to have all the answers, but here are a few writing tips I’ve picked up along the dark and winding way through the forest. If you’re working on something spooky or supernatural, or you’re curious about what makes a ghost story, I hope these tips might be interesting!

1. Use your own fears and fascinations

When you’re writing a spooky story, always write what scares you. Try to identify the things that make you uneasy, anxious, and afraid. Were you told a ghost story as a child that now sounds ridiculous but left you unable to sleep for days? Think about the core of what scared you when you heard it.

Shirley Jackson, one of the very best authors of mysterious horror stories with gothic undertones, said:

I have always loved to use fear, to take it and comprehend it and make it work and consolidate a situation where I was afraid and take it whole and work from there.

—Shirley Jackson

That’s why my third novel, The Clockwork Girl, is about automata and the uncanny, and my next is about poltergeists and the rise of Fascism. They had to be subjects that scared me.

So don’t just fall back on a common theme of a classic haunted house or a stereotypical ghost story. Instead, work out what makes you uneasy and communicate that to the reader. That way, you’ll frighten them senseless.

2. Choose a setting that can become its own world

The setting in a ghost story needs to be somewhere that has the capacity to become its own frightening world.

That doesn’t mean it has to be a dilapidated haunted house, a spooky castle, an abandoned nursing home, or a former family house that’s crumbling into the undergrowth—although, of course, it is, to great effect in plenty of spooky novels. Some stories I can’t forget that do this wonderfully include Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, Sarah Waters’s The Little Stranger, and Laura Purcell’s The Silent Companions.

Your setting could be the daunting Himalayas, as in Michelle Paver’s Thin Air, or the frozen wastelands of the Arctic, as it was in her novel Dark Matter and in the book that became a successful TV series: The Terror by Dan Simmons. It could be the barren and hostile landscapes of Andrew Michael Hurley’s Starve Acre. It can also be a New York high-rise apartment, as it is in Rosemary’s Baby by Ira Levin.

The secret, I think, is to make that place its own world, removed from reality and somehow ‘other.’ Islands are particularly good settings, and it is no coincidence that they recur in many ghostly tales: Shutter Island by Dennis Lehane, Duma Key by Stephen King, Summerisle in The Wicker Man, Eel Island in Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black, and the Isle of Skye in my own novel, The Story Keeper.

The secret, I think, is to make that place its own world, removed from reality and somehow ‘other.’

—Anna Mazzola

3. Spend time with your haunted landscape

You then need to cultivate that setting to make it your own world, where terrifying things can occur and cannot be stopped.

Andrew Michael Hurley says:

Place has been the starting point of all my novels so far and I always try to make landscape a living element in the story—another character, as it is in Wuthering Heights and in much of Thomas Hardy’s work too.

—Andrew Michael Hurley

He advises: ‘You have to spend time with the landscape in order to get to know it that well.’ I agree with that—I spent much time on the Isle of Skye when writing The Story Keeper, breathing in the air, walking the hills my characters would have walked, listening to the trill of the birds, the wash of the waves in the bay.

Michelle Paver does the same, going on a research trip once the first draft is complete. For Thin Air, she went mountaineering in the Himalayas and experienced for herself the strange, haunted creaks a tent makes in the night, and how confusing outside sounds become when you’re under canvas.

If you can’t visit your setting, read as much as you can about it, pore over maps, and watch YouTube videos. Stef Penney wrote The Tenderness of Wolves without ever leaving her house. She said she did almost all the research for her novel in the British Library and, being agoraphobic, had not set foot in Canada at all. Instead, she created the landscape in her mind.

4. Drip unease throughout your writing

Writing a ghost story or a haunted tale is very much about atmosphere: the mood, the quality of the air, the sounds, the scents, and tense awareness that this is a place where anything could befall your characters.

One way to create unease is to insert key details which will make most people feel the chill of being scared. Let them sense the danger by keeping one step ahead of your protagonist, and they will be gripping the pages of your book for dear life in fear of what’s coming next.

You can do this by adding imagery that fits with the dark theme of your novel or by having your narrative give hints of the danger ahead that will lodge in the reader’s mind.

It was only when I re-read Sarah Waters’s The Paying Guests that I realized she’d shown us the murder weapon not just in the first half but in the very first chapter, forewarning us of what was to happen.

In horror fiction, there tend to be even bigger clues that something horrendous is coming. In Stephen King’s The Shining, Danny can see certain elements in the future: the word Redrum, the mallet. We know the truth, just as he does—that terrible things are coming. In Donna Tartt’s brilliant The Secret History, we know right from the word go how this is going to end. The question is how we get there.

The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation. He’d been dead for ten days before they found him, you know.

—Donna Tartt, The Secret History

5. Create suspense

In order to have your reader sitting on the edge of their seat, you need to build not just unease but suspense. The ghost, monster, or danger needs to stalk slowly closer to us, growing more frightening as the story reaches its climax.

As with a thriller, you need to keep the reader asking questions, and you need to keep withholding information from them. For example:

- Why isn’t your protagonist’s husband home yet?

- Is that a log floating in the river that just seems to look oddly like a body?

- Who is the person who keeps appearing outside your main character’s office but never showing their face?

- Why does their mother suddenly sound so odd on the phone?

Dangle your reader on the hook and maintain that sense of unease. I always find that it takes me several drafts to determine how much information to provide and how much to hold back.

Peter Straub, author of Ghost Story, says:

It is very important to me to keep building up a gathering head of steam so the reader does really wonder, ‘What will happen next?’ There is very little difference between the way that feels in the basic crime or spooky context. It’s the same sense of anxiety, uncertainty, facing the unknown, being puzzled—in short, a layer of suspense.

—Peter Straub

6. Dissect the best spooky literature

In terms of how you master all these techniques, the answer is to read as many ghost stories, gothic novels, horror titles, and classic literary tomes as you can.

Once you’ve decided on your favorites, go back and carry out an autopsy, dissecting them to work out why and how they work.

I have read the likes of Du Maurier, Shirley Jackson, and Sarah Waters again and again, trying to ascertain how they did it so well.

When you re-read, you will pick up the first clues and hints of danger that you might have missed on the initial read, and you can identify how the writer has dripped mystery and menace into the text until the fear is a terrible flood. You’ll understand the secrets of a great ghost story—and how to scare the reader—intimately and intuitively.

7. Keep the monster in the cupboard

Perhaps the most powerful weapon in a writer’s arsenal is the unknown—using the reader’s own wicked imaginings. Only you know what really scared you about that ghost story when you were younger and what still scares you now, so only when left to your own devices can you begin to summon it.

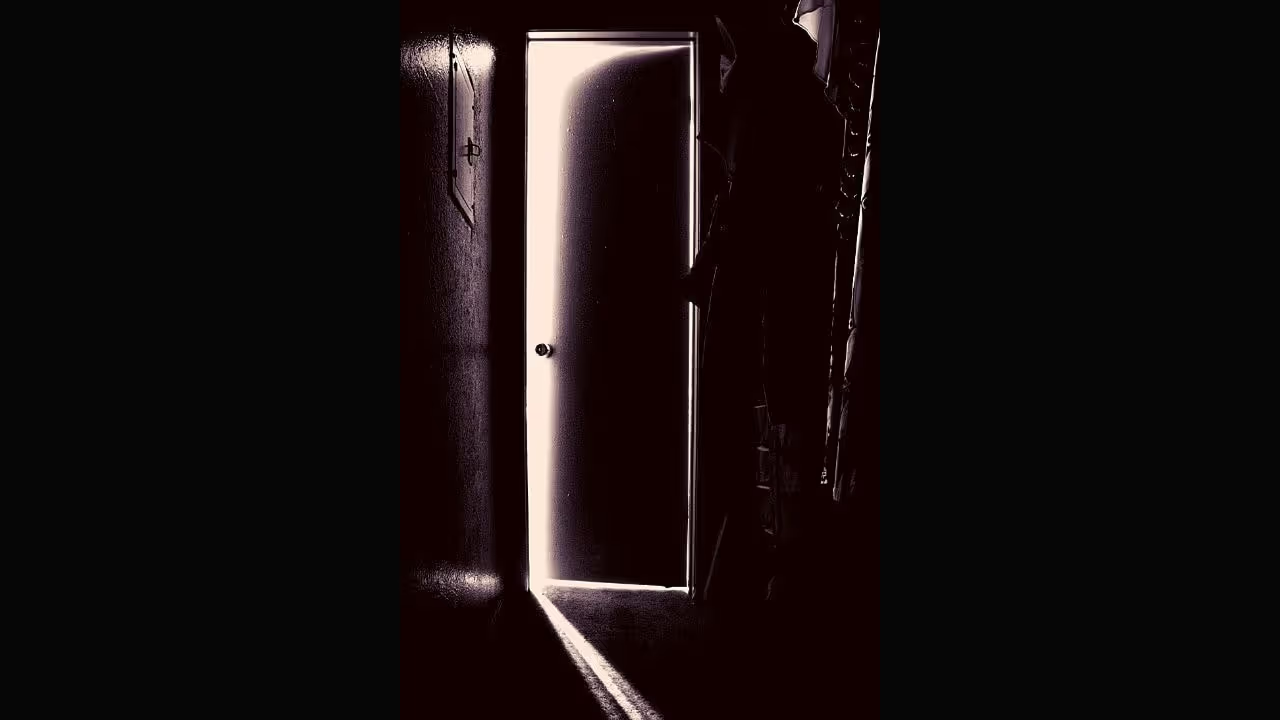

Often, the incredible thing about a compelling ghost story is that the terrors are glimpsed or imagined in the cracks rather than leaping out of the shadows to grab you by the throat. Let your reader guess what lurks behind the door in the middle of the night, but don’t paint it for them, or at least don’t complete the picture.

Often, the incredible thing about a compelling ghost story is that the terrors are glimpsed or imagined in the cracks rather than leaping out of the shadows to grab you by the throat.

—Anna Mazzola

Similarly, in Michelle Paver’s Dark Matter, we hear the figure, we smell it, we fear it, but we never fully see it. Uncertainty is the black heart of terror, and if you paint the full picture, you take that away.

Where there is no imagination, there is no horror.

—some bloke called Arthur Conan Doyle

8. Experiment with point of view

Take time to work out where to situate your reader. A most unnerving ghost story tends to have a close narratorial viewpoint: we view events from the eyes of the narrator. We see what they see, hear what they hear, and consequently fear what they fear.

In Du Maurier’s Rebecca, we never even know the name of the narrator because we are there—we walk about the halls and staircases of Manderley, and we quake in the wake of Mrs. Danvers.

In Sarah Waters’s The Little Stranger, the impact of the ending is all the more awful because we are Faraday—or, at least, we are almost Faraday, when he looks in the mirror and sees his own face. But we understand what Faraday does not.

9. Focus on the psychology

It is not just seeing through the narrator’s eyes but being inside their head.

For me, the most masterful spooky literature has a strong psychological element. These are novels in which what is real and what is not is a battle within the mind of the protagonist.

Years after it was written, people continue to argue over whether the ghosts in James’s The Turn of the Screw were merely the product of the Governess’s imagination. Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper continues to terrify because we go steadily mad with the imprisoned protagonist. Rebecca remains a bestseller because the dead Rebecca skews the narrator’s mind and our own perception of events as powerfully as if she had come back to life and was still walking about Manderley.

The most masterful spooky literature has a strong psychological element. These are novels in which what is real and what is not is a battle within the mind of the protagonist.

—Anna Mazzola

10. Give us main characters to care for

Of course, none of this will work unless, at the center of it all, you have characters we care about.

We’re invested in the outcome of a story, often seeing the character as a friend to whom we want to yell ‘RUN!’—only if we have some emotional stake in its context. As Stephen King says:

You have got to love the people. There has got to be love involved, because the more you love—kids like Tad Trenton in Cujo or Danny Torrance in The Shining—then that allows horror to be possible.

—Stephen King

And it’s not only the protagonists who have to seem real but the monsters themselves.

The most terrifying villains and ogres are those who are not so far removed from the normal. They are almost human, almost us, but with deformities, often of mind, that make them truly terrifying. Just think of vampires, like the erudite antagonist of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Or, indeed, the startlingly intelligent protagonist Mary Shelley created (not to mention his monster).

The most terrifying villains and ogres are those who are not so far removed from the normal.

—Anna Mazzola

And finally, for a bonus tip...

11. Ambiguity and endings

For me, the most satisfying ghost stories leave a window (or sometimes a creaking door) open for the possibility of an as-yet-unknown reality. There is no neat tying-up of ends but an ambiguity that leaves us to question what has really happened and what is really real.

Again, it leaves us, the reader, to think for ourselves and imagine our own ending. We’re unlikely to sleep well afterward.

Welcome home, writers. Join us on the world’s best creative writing courses to create, write, and complete your book. Sign up and start today.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)