Leo Tolstoy is one of the most admired authors in the canon of western literature, and his titles are some of the most famous in fiction. For example, War and Peace and Anna Karenina (the focus of this blog post) have been admired as some of our finest works of literature since the Russian empire came to its end. They represent not only Russian society at the time of writing but explore the unspoken thoughts of readers worldwide even today. Leo Tolstoy also wrote many short stories and novellas, including The Death of Ivan Ilyich, The Kreutzer Sonata and Family Happiness. His earlier works were in part informed by his experiences of the Crimean war, but as time went on and his style developed, we see different preoccupations emerge.

If you’re interested in learning more about Leo Tolstoy, and the intricacies of his writing style, you’re in luck. In this blog post, we’ll be giving some careful consideration to Tolstoy’s style and process to try and uncover what makes this Russian writer so remarkable.

Leo Tolstoy’s works reflect his moral explorations

In the 1870s, Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (1828 - 1910) experienced a profound moral crisis. During the writing of Anna Karenina, he went through a personal metamorphosis from sensualist to ascetic. This had a dramatic effect on his literary output, and the books that follow it are of a different tone, and more didactic. In these later works, Tolstoy developed a radical anarcho-pacifist Christian philosophy. Ultimately, this resulted in his excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1901.

Writing Anna Karenina required many drafts over four years, and evolved from a rather superficial treatment of a ‘fallen woman’ to a more nuanced and sympathetic evocation of Anna, the literary heroine.

We can see how Tolstoy seeks to give the story greater depth over those drafts. The constant in the concept was Anna herself, though her character changed in the early drafts.

With Anna, we see Tolstoy’s ability to put his finger on his own flaw or failing; the sensualist. Writing Anna enabled him to see his own flaw. A great writer is also profoundly aware of the failings of human nature, and this awareness begins at home.

How to complete a work of fiction?

There are one or two ways to write a book.

1. A fast first draft and multiple successive drafts

For this method ideally you need a sounding board – an agent or ambitious and serious writing friends to tell you: no, you’re not there yet, go further.

Think F. Scott Fitzgerald, J.M. Coetzee and Leo Tolstoy.

2. Slow and steady

The Graham Greene and Ernest Hemingway method of 500-650 a day every day.

Write in the way that works for you

Our Ninety Day Novel Class allows for both methods. Yes, you are guided to finish a first draft in ninety days, but the principle of our method is to make you work the way a working author really and truly works as the basis for success.

It is commonly held that it takes ninety days to form a habit. After ninety days with us, you will be a working writer, whatever your day job or duties.

Working in seasons and drafts, harnessing the energy of them in bouts of activity, is a great way to go.

Leo Tolstoy’s writing style comes through craft, not genius

It is consoling to see that a writer like Leo Tolstoy raised his game dramatically between drafts. His first draft was thin.

Writing is not an act of genius, as the defeatists and art snobs pretend, but a craft that requires ambition and willpower. It is work in which passion is tempered by judgement, and this is the very heart of the method we embrace within our online fiction writing courses, by which writers come to understand through practice that the back and forth of those two inner forces drives advancement.

I’m going to show you the evidence, but let me just remind you of the enormous claim to genius Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina has. It tops the list for masterpieces of literature as chosen by 125 other writers, Time Magazine, Encyclopedia Britannica, and Wikipedia.

One of the finest novels

The best novel ever written.

—William Faulkner

(Asked to name the top three novels of all time, he responded: “Anna Karenina, Anna Karenina, Anna Karenina.”)

A perfect work of art.

—Fyodor Dostoyevsky

One of the greatest love stories in world literature.

—Vladimir Nabokov

The point of departure

Tolstoy’s wife, Sophia Andreevna, noted in her journal on 23 February 1870 that her husband said he had:

Envisioned the type of a married woman of high society who ruins herself. He said his task was to portray this woman not as guilty but as only deserving of pity, and that once this type of woman appeared to him, all the characters and male types he had pictured earlier found their place and grouped themselves around her. “Now it’s all clear,” he told me.

In January 1872, a few miles from his estate, Anna Stepanovna Pirogov threw herself under a goods train at a railroad station, after her lover abandoned her.

Anna Pirogova was a distant relation of Tolstoy’s wife. She had become the housekeeper and lover of his friend and neighbour Alexander Bibikov. Bibikov had told Anna he was going to marry his son’s governess, an attractive German girl. In a rage of jealousy and anger, Anna sent him a note accusing him of being her murderer before taking her own life.

Tolstoy went to the autopsy. He was distressed by seeing the mangled corpse. This was one of the first railway suicides on Russia’s expanding network, which had increased to over 10,000 miles of track by the 1870s.

Leo Tolstoy was struggling

Tolstoy had been struggling with a book on Peter the Great and lost enthusiasm for it.

Reading a Pushkin short story gave him a moment of sudden clarity as to how to begin a new undertaking in fiction. An opening sentence ‘The guests arrived at the dacha’ caught Tolstoy’s eye. He was riveted by how Pushkin got straight down to the action, without even bothering to set the scene first or describe the characters.

After thirty-three false starts with Peter the Great, this was a revelation. It gave him renewed appetite to make a new start, but on a new subject, closer to home.

Concealing the autobiographical nature of Tolstoy’s works

Of course, its autobiographical nature was nattily concealed by use of the other gender. Flaubert said Madame Bovary was him. It amuses me that reviewers and readers, prone to claiming the main character is a manifestation of the author as if this makes it all so easy, are duped when one writes as the other gender.

A recommendation we make to our writers in our courses is that they start with the moral flaw of the main character. Often, you’ll use one of your own.

Tolstoy’s later works lack the sense of humour and sagesse of folly we love in Anna. Once he began to see the life behind the fallen woman, his style developed to become more fully rounded and sympathetic than in any of the other novels besides War and Peace.

Let’s look at how hard he found this project to give you good cheer.

Every novel is new. True for Tolstoy too

Tolstoy was so enthusiastic about his new approach inspired by Pushkin combined with the meaningful subject matter, he thought he’d nail the book in fifteen days! Tolstoy began with his vigorous first chapter – a scene at the opera – and sketched out eleven further chapters.

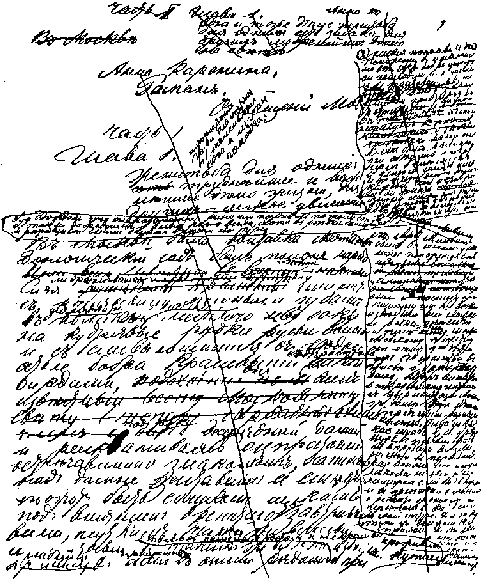

The drafts

But the book took him four more years of work.

Much that had come together so suddenly through the agency of ‘the divine Pushkin’ was altered or rejected.

Settling the cast

In the first versions, Anna (variously called Tatiana, Anastasia, and Nana) is a rather fat and vulgar married woman, who shocks the guests at a party with her shameless conduct with a handsome young officer. She laughs and talks loudly, moves gracelessly, gestures improperly, is all but ugly – ‘a low forehead, small eyes, thick lips and a nose of a disgraceful shape …’ Her husband (...) is intelligent, gentle, humble, a true Christian, who will eventually surrender his wife to his rival, Gagin, the future Vronsky. In these sketches Tolstoy emphasized the rival’s handsomeness, youth and charm; at one point he even made him something of a poet. The focus of these primitive versions was entirely on the triangle of wife, husband and lover, the structure of the classic novel of adultery.

—Richard Pevear

He started a new draft of the beginning. This time he called his heroine Anastasia (‘Nana’) Arkadyevna Karenina, and replaced her yellow lace gown with the black velvet she will wear to the ball in the final version. Her husband was now firmly called Alexey Alexandrovich, but her lover’s name was switched from Balashov to Gagin.

Tolstoy ended up discarding this draft, but he would save up the detail of the caught lace for Anna to unhook in the final version of the novel, when she is leaving Princess Betsy’s soirée after her fateful encounter with Vronsky.

—Rosamund Bartlett

The introduction of some of the most memorable characters

The story of Levin and Kitty was absent from early drafts. There were no Shcherbatskys, the Oblonsky family barely appeared, and Levin was a minor character.

In the early versions, Tolstoy clearly sympathized with the saintly husband and despised the adulterous wife. As he worked on the novel, however, he gradually enlarged the figure of Anna morally and diminished the figure of the husband; the sinner grew in beauty and spontaneity, while the saint turned more and more hypocritical. The young officer also lost his youthful bloom and poetic sensibility, to become, in Nabokov’s description, ‘a blunt fellow with a mediocre mind’. But the most radical changes were the introduction of the Shcherbatskys – Kitty and her sister Dolly, married to Anna’s brother, Stiva Oblonsky – and the promotion of Levin to the role of co-protagonist. ...The novel they weave together goes far beyond the tale of adultery that Tolstoy began writing in the spring of 1873.

—Richard Pevear

On 11 May 1873 Tolstoy wrote to tell his friend, the philosopher, Nikolay Strakhov, that he had spent over a month working on a book that had nothing to do with Peter the Great.

He emphasised that he was writing a proper novel, the first in his life. He had been writing the word roman (‘a novel’) at the top of the page on each new draft of his opening chapter.

At this early stage, he was still very excited by his new project, which he told Strakhov completely ‘enthralled’ him.

Third draft

The turning point in the creation of the book happened in the third draft, when Levin was introduced. At that point, it became the tale of two married couples. In fact, Tolstoy’s title for the work at that point was Two Marriages.

Levin’s significance: autobiography as a source

We see the introduction of Levin and the rural lifestyle on his family’s estate as a counterbalance to the high society affair, and a depiction of a very different family life.

Levin is a self-portrait for Leo Tolstoy. The other side of the writer. He has the same ideas and opinions, the same passion for hunting, the same almost physical love of the Russian peasant, and many of the events and experiences of Leo Tolstoy are assigned to Levin.

About this time he stopped writing his journal since he felt he could explore his thoughts and feelings and experience directly within the work.

Anna’s development: SHOW don’t TELL

In the earlier drafts, Anna was more fully explained. Tolstoy described her past: how she came to marry, at the age of eighteen, a man who was twelve years her senior... He stated explicitly that ‘the devil had taken possession of her soul’, that she had known these ‘diabolical impulses’ before, and so on. This a classic example of the fiction mandate to show, don’t tell.

The Homeric influences of the character of Helen of Troy whose beauty proved so dangerous was very much alive in the laboured and reverential prose of his writings at this time. Only a few traces of this detail remain in the final portrait of Anna.

As Tolstoy rewrote, his writing style became less direct and didactic. He removed most of the details of her past, her motives, and replaced them with hints and suggestions. She is elevated from pitiful and pathetic fallen creature to heroine. We typically see this elusive description of main characters when an author elevates them morally, as I explain in my blog post on creating the hero in a novel. This was the careful construction of a person worthy of empathy, not merely repudiation. A refreshed approach not only showed how a socially correct life might spell doom for many women, it afforded a new and deep insight into human nature. Tolstoy recognised that an enlivened soul occasionally deviates from social forms. By offering this sympathy, asking the same of us, he directly communicated with readers of all backgrounds and classes throughout the world.

You may be familiar with Hemingway’s iceberg theory, which we explore in our creative writing courses for character development. Some deft brushwork will do to show us aspects of our characters, focusing on the unusual or distinct to highlight with ‘light’ and ‘shade’ their individuality.

Fourth draft

The addition of conflict

In the fourth draft of 1873, Leo Tolstoy made a new stab at an opening.

This draft begins with the familiar scene of a husband waking up after rowing with his wife the night before, after she discovers his infidelity. Anna comes to Moscow as peacemaker, and she meets Gagin (later Vronsky) at the ball.

But still Tolstoy was not satisfied: there was no tension in the relationship between the Levin and Vronsky prototypes, as they were friends. He decided to change their names to Ordyntsev and Udashev, and now made them rivals for Kitty’s hand rather than friends. It was time to try another beginning. Tolstoy took out a fresh sheet of paper and started a fifth opening draft.

—Rosamund Bartlett

Fifth draft

He reworked the crucial opening scenes four times to get them exactly right, and these were the first chapters he gave Sonya to make fair copies of.

They went to be bound. Everything else stayed in draft form.

On 9 November the Tolstoys suffered their first bereavement with the sudden death of the youngest son, the previously healthy eighteen-month-old Pyotr (Petya). (In total, the Tolstoy’s would have thirteen children, though tragically only eight survived childhood.) Life, and death, happen to authors too.

At the end of 1873, he decided he would go ahead and print the first part in book form, without prior publication in a journal.

In January 1874 Tolstoy went to Moscow to draw up an agreement for publishing Anna Karenina with Mikhail Katkov’s printing house.

Leo Tolstoy became distracted from his work

During this time, the Russian author was also immersed in his educational crusade, publishing provocative articles on the subject, and his enthusiasm for his work of fiction waned again. Indeed, on 10 May 1874 he informed his friend Strakhov that he no longer liked it.

His aunt Tatyana Alexandrovna – Toinette, his surrogate mother – died on 20 June. ‘I’ve lived with her my whole life. And I feel awful without her,’ he wrote.

Strakhov tried to rekindle his interest in Anna Karenina in July 1874 when he came to stay, but Tolstoy had lost momentum which he directly communicated when he referred to his novel as ‘vile’ and ‘disgusting’.

Sixth draft

When he got back the proofs of the thirty chapters that had already been typeset he decided to start the whole beginning again.

He broadened its scope and in this new style introduced topics that interested him, such as ploughing techniques, but his work on the book was now proving irksome.

He didn’t manage to complete the book in 1874, in 1875, or 1876.

The last sentence was not written until 1877.

In all, Tolstoy produced ten versions of the first part.

Fatigue

Subscribers to the Russian Messenger started reading Anna Karenina at the beginning of 1875, when the first chapters appeared in the January issue – before the novel was complete.

The first instalment ended with Anna leaving the ball early, having danced the mazurka with Vronsky, bringing Kitty’s dreams crashing to the ground.

In the second instalment in the February issue of the Russian Messenger, readers sympathised with the grieving Kitty and Levin, both spurned. There were further instalments of Anna Karenina in March and April 1875, but readers had to wait eight months for the next chapters to be published, as Tolstoy had not finished them.

He took a couple of months away from writing and forced himself to return to the ‘boring, banal’ story in the autumn of 1875.

He wrote to Strakhof:

I must confess that I was delighted by the success of the last piece of Anna Karenina. I had by no means expected it, and to tell you the truth, I am surprised that people are so pleased with such ordinary and EMPTY stuff... It is two months since I have defiled my hands with ink or my heart with thoughts. But now I am setting to work again on my TEDIOUS, VULGAR ANNA KARENINA, with only one wish, to clear it out of the way as soon as possible and give myself leisure for other occupations, but not schoolmastering, which I am fond of, but wish to give up; it takes up too much time.

Despite feeling as fed up with the book as with a ‘bitter radish’, he pressed on.

At the end of October, Sonya fell ill with peritonitis and went into labour. Varvara, born three months premature, died a few hours after she was born.

‘Fear, horror, death, children cavorting, eating, fuss, doctors, falsity, death, horror’ was how Tolstoy defined the situation at Yasnaya Polyana in a letter to friend, Afanasy Fet.

Another third of the novel was printed in the first four issues of the Russian Messenger in 1876. The April issue contained a substantial section of Part Five, ending with a chapter recounting the last days of Levin’s brother Nikolay. Tolstoy drew on his own personal experience subsequent to the three deaths he had suffered.

The April 1877 issue of the Russian Messenger contained the last chapters of Part Seven, which end with Anna’s death. They were greeted with wide acclaim.

In 1878, when the novel was nearing its end, he wrote again to Strakhof:

I am frightened by the feeling that I am getting into my summer mood again. I LOATHE what I have written. The proof-sheets for the April number now lie on my table, and I am afraid that I have not the heart to correct them. EVERYTHING in them is BEASTLY, and the whole thing ought to be rewritten,—all that has been printed, too,—scrapped and melted down, thrown away, renounced. I ought to say, ‘I am sorry; I will not do it any more,’ and try to write something fresh instead of all this incoherent, neither-fish-nor-flesh-nor-fowlish stuff.

The verbal DNA of the first chapter

In our blog on The Great Gatsby, you will read how Scott Fitzgerald intended to be ‘patterned’ and carefully coded, in modern parlance.

As we’ve seen, Tolstoy laboured over Anna Karenina. Let’s look at the words with which he was most heavy-handed in a very short first chapter of just 950 words.

The famous opening line is there to tell us this is a story about family. (The Russian author was casting Russia as ‘the family’.)

The matter of the wife (and the role of the wife) amounts to 16 mentions, and is the most significantly used word by far. It’s a fairly uncomplicated style with which to set up his key themes.

Wife - 8 times

Smile - 6

Husband - 5

His wife - 5

Family - 4

House - 4

Sofa - 4

Face - 4

Hand - 4

Household - 3

Room - 3

Dinner - 3

Quarrel - 3

Wifes - 3

Bedroom - 3

Study -3

Look how warm and cosy and intimate this set up is! With his careful construction of a widely-relateable milieu, Tolstoy meant to draw us close into the bosom of a family home.

Thus it is that one of the greatest writers of all time begins the novel that is better loved arguably than the grander War and Peace with a humble and cosy start. His light shines on the lives all men live, as he reaches out to readers throughout the world.

To write like Tolstoy is not about applying techniques, it’s about allowing us into the unspoken thoughts and lived experience of one person at a time.

Remember, Tolstoy’s inspiration for writing the novel began with the simplicity of Pushkin’s opening line. This matter-of-fact opening provided the resurrection of his fiction and one of the great works of literature.

One of the greatest writers is also the simplest.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)