Story endings are exciting, rewarding, and—let’s be honest—sometimes scary to write. If you’re struggling to compose the last lines of your novel, you’re not alone. It can be hard to know exactly when and where to end a story. You’re battle-weary, you can’t see the wood for the trees, it’s the 45th draft... No wonder you’re going over and over those last few words!

Don’t worry. We’re going to help you come up with a satisfying ending and a last line your reader will think about long after the book is closed. Whether you’re going for a surprise ending, a cliffhanger ending, or a straightforwardly resolved ending, the tips and ideas in this blog post will help give your main story the finale it deserves.

Your task as the author is to tie together all the loose ends to form a satisfying finish, whether it be an ambiguous ending, a sad ending, or a joyous one. Much of this will depend on your genre—romance readers, for example, will expect a satisfyingly happy ending in which the couple finally gets together. In literary fiction, an unresolved ending might be more acceptable. In a murder mystery, the reader will be left wanting if we don’t find out who committed the murder and why.

You are the only person who can write it

Whatever genre you’re writing in, you need to finish your story arc in a satisfactory way and give your characters some sort of resolved ending. The final chapter needs to provide resolution and closure in the reader’s mind, even if you don’t fully answer every single question.

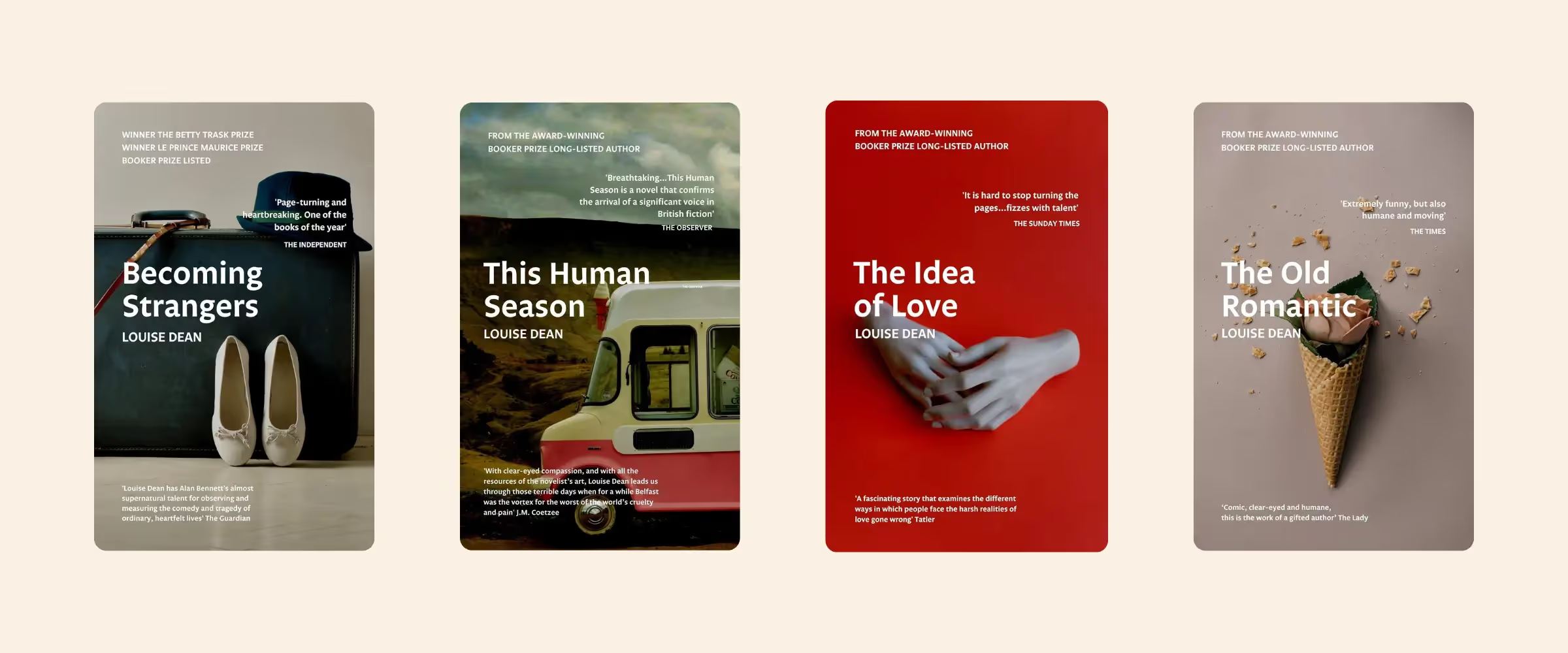

In the first part of this blog, The Novelry’s founder, Louise Dean, will share her expert tips on what makes a good ending (something you can explore in deeper detail in writing coach Mahsuda Snaith’s blog on how to wrap up a story, as well as writing coach Kate Davies’s article on how to map your way to a satisfying climax).

Then, we’ll take a look at some of the best and most famous final lines in literature—the ones most well-known and loved among readers and writers. Our team of writing coaches and publishing editors has also contributed their favorites for a noteworthy list of closing lines of novels to inspire you with your own.

Pen at the ready? Over to Louise...

.avif)

How neat is a good ending?

You come to what you think is the final page, and put down your proverbial pen to survey your work. The story makes sense.

But your worry may now be that the story makes too much sense at the expense of mystery. So you’ll want to go back to a few key moments to make them accurate and translucent—shimmering—to leave room for the reader.

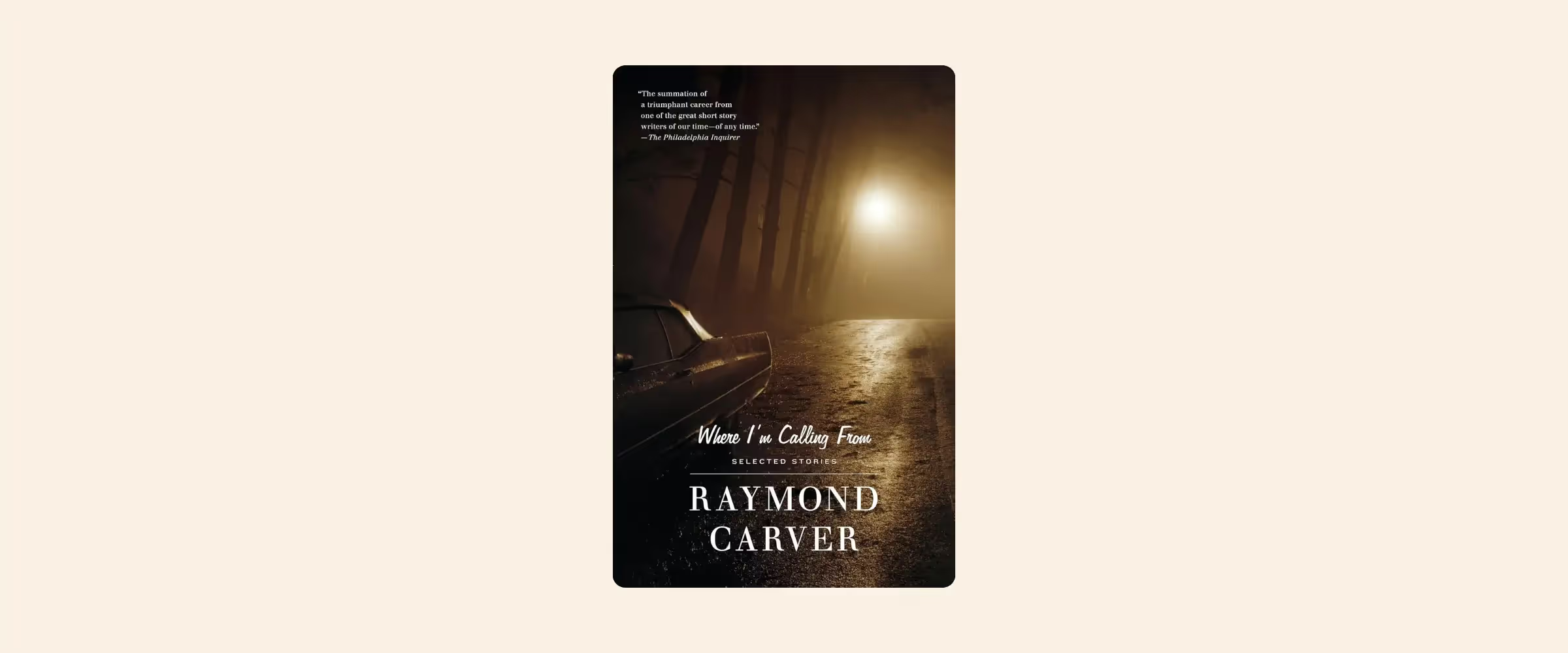

Learning the art of a great ending from Raymond Carver

I like to perform these last checks while reading Raymond Carver on loop during the last week or so before I hit send. In my eyes, he was the master when it came to making space for the reader.

I forget who passed along a copy of Babel’s Collected Stories to me, but I do remember coming across a line from one of his greatest stories. I copied it into the little notebook I carried around with me everywhere in those days. The narrator, speaking about Maupassant and the writing of fiction, says: ‘No iron can pierce the heart with such force as a period put just at the right place.’ When I first read this it came to me with the force of revelation. This is what I wanted to do with my own stories: line up the right words, the precise images, as well as the exact and correct punctuation so that the reader got pulled in and involved in the story and wouldn’t be able to turn away his eyes from the text unless the house caught fire.

—Raymond Carver, Where I’m Calling From

It’s the key to the mystery of a story, that space. It’s what makes it a living space. There’s a haunted quality to the endings of Carver’s short stories. A triple presence. Writer (or narrator), reader, and the sense of being watched by another external presence of such power that sometimes Carver’s unfanciful characters fall to their knees.

Carver writes to arrive at this mountain-top, a place of greater sight.

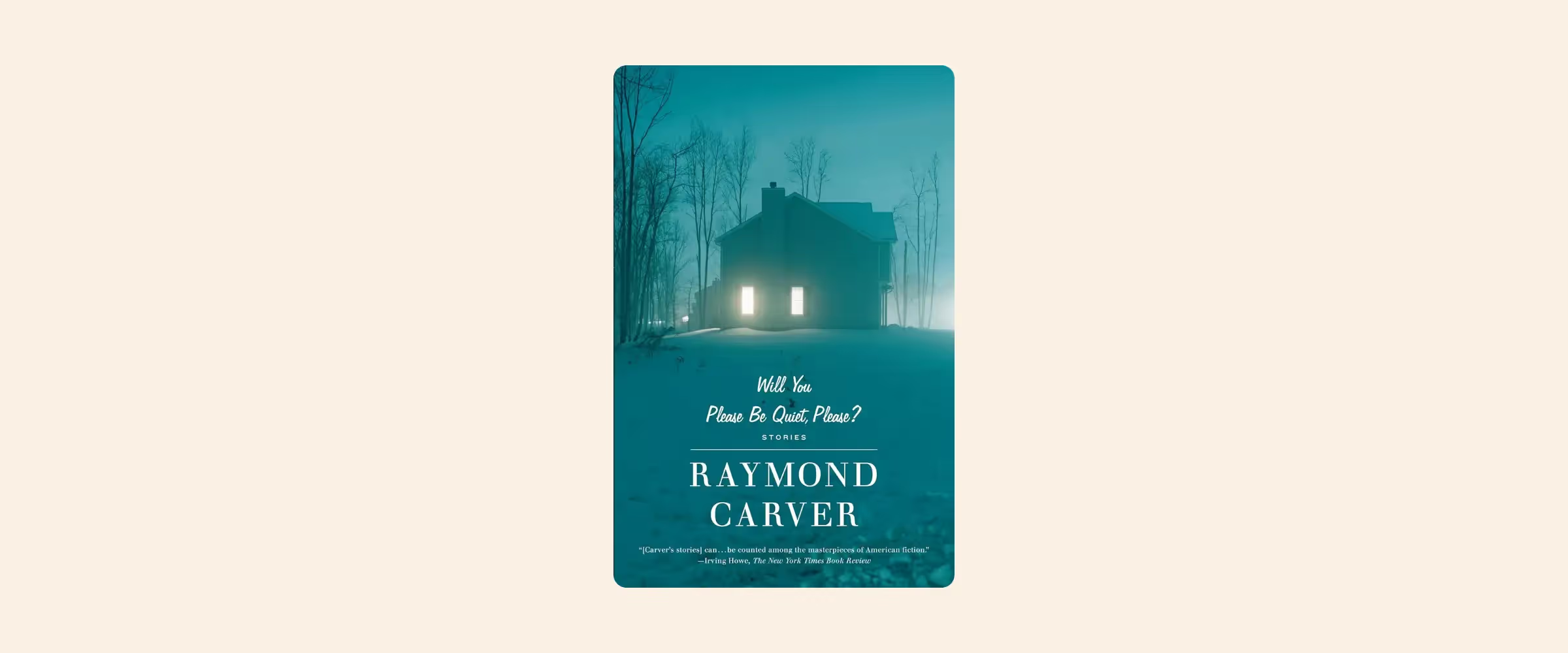

In his story ‘A Student’s Wife’ (which features in the collection Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?), the girl rises early:

...she had seen few sunrises in her life and those when she was little. She knew that none of them had been like this. Not in pictures she had seen nor in any book she had read had she learned a sunrise was so terrible as this. (...)

She wet her lips with a sticking sound and got down on her knees. She put her hands out on the bed.

‘God,’ she said. ‘God, will you help us, God?’ she said.

—Raymond Carver, ‘A Student’s Wife’

A good story needs great characters

I check through my work to ensure we get up close and personal, inside the main character or characters like this.

It seems to me there are two ways to push them so hard that we know them intimately. One is through their own (horrified) realization of who they are and what they are. (The rocks you throw at them in the plot are there for this purpose.) The other is grace. Insight comes to them as a mystery.

When I think about Carver, I tend to think of the imprecations and exhortations people make of each other in their couples in his stories, pithily expressed in even the title of the short story ‘Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?’ (note the double please).

When I read Carver, I notice how often the characters are in the dark, literally, with their thoughts and how often they turn to face the wall. This may reflect the many unhappy years Carver spent drinking heavily, not nearly as productive as when he quit. They’re trying hard to see something they can’t see.

Just as he started to turn off the lamp, he thought he saw something in the hall. He kept staring and thought he saw it again, a pair of small eyes. His heart turned. He blinked and kept staring. He leaned over to look for something to throw. He picked up one of his shoes. He sat up straight and held the shoe with both hands. He heard her snoring and set his teeth. He waited. He waited for it to move once more, to make the slightest noise.

—Raymond Carver, ‘What’s in Alaska?’

It’s the movement, the turning from the difficulty in the world, workplace, home life, to the wall and the dark for help, this tossing and turning, one might say, that characterizes the complexity of existence as individuals.

We try to get help, we don’t know where to get help, we feel powerless.

It seems important to me that the most apparently powerful characters seem the most lost, off stage and yet in the reader’s sight.

{{blog-banner-2="/blog-banners"}}

A good ending for your main character

The ending is a place of insight that affords our hero or heroine a sense of peace—a temporary stay against confusion, one might call it.

That’s how I think of it, for my books. I don’t ask for more than that for them, as I don’t ask for more than that for myself. I’ll have asked lots of questions in my story about how to live, and what to live for, but finally, just a little space is cleared for the reader to consider their own answer.

For me, that’s how you want to leave it, like the room was prepared for them all along, and the covers are turned back, and they can rest now.

Probably their greatest initial problem or truest concern finds a moment’s reprieve, but I try not to dare to suggest there is more than that. My stories are, perhaps sadly, for adults and not children, and maybe this is what defines them. The temporary peace and space.

I write my novels with people all around me, wanting this, wanting that, talking at me. It’s called being a single working mother. I am surprised I don’t have a hunched back from flinching away to try to get something down straight, in seconds sometimes.

So the gift I give my main character is very valuable to me. Sure, we dream of hours, days, time to work. But in reality, we make do with the dark, the wall, the tossing and turning, the snatching of a few moments’ peace to see.

Each of us has a private world, and the only difference between the reader and the writer is that the writer has the ability to describe and dramatize that private world. As a writer, I write to see. If I knew how it would end, I wouldn’t write. It’s a process of discovery.

—John McGahern

How a great story ends can leave a lasting impression

Is it good? This story of mine? I don’t know. I don’t even know what that means, but if it means how many and who will think it’s good, I don’t know that I care.

Of course, I have cared, en route, very much. But not now. For this is mine, my way of seeing things. I have chosen to show these things. The moment when you have to put it down, you say to yourself that it’s whole, and it says what you wanted to say in this season, but the season is ending.

If I meant for this phantom twin of mine—the heroine—to find tenderness or conviction, did they find it? And are the others on the battlefield left as they should have been, either at the campfire or limping away? Did we fight the good fight?

Was there a moment of sense caused by sorrow? Did we pity the nasty piece of work? Did we embrace the dark to find the light?

Have I been honest where I needed to be, and clean where I was able? Not completely clean—a story is a contrivance—but clean enough? If ever one of my children picks it up, will they know from it that I loved them? And that I was happy doing what I loved, and I didn’t want more than what I needed...? And will that encourage them to find their way through, too?

Finally, does it offer hope? Does it say: we are more alike than we know?

.avif)

How to know when you’ve reached the end of a story

Am I done?

The ideas that come to you during your day, on the dog walk, in the shower, at the fridge door—they start to thin out, and you’re even starting to rule some out. When I say, ‘No, I don’t think I’ll use that,’ I know the tide has turned on the writing. When another voice or another idea starts coming to me, I think, ‘Yes, the season of this novel has passed and a new one is beginning.’

Then, one morning, I wake with some crazy, bold, broad idea in my head—a whole new world—and I know it’s time to say goodbye to the old novel, and hello gorgeous!

Why not start your next love affair by taking a novel writing course at The Novelry?

On ending novels

E.M. Forster said:

Ends always give me trouble. Characters run away with you and so won’t fit in to what is coming.

—E.M. Forster

In Aspects of the Novel, he wrote that nearly every novel’s ending is a letdown:

This is because the plot requires to be wound up. Why is this necessary? Why is there not a convention which allows a novelist to stop as soon as he feels muddled or bored? Alas, he has to round things off, and usually the characters go dead while he is at work.

—E.M. Forster

Graham Greene found beginning a story more unnerving than ending it:

After living with a book for a year or two, he [the novelist, and ideally the reader, too] has come to terms with his unconsciousness – the end will be imposed.

—Graham Greene

That surely is right. The end is imposed. It is no longer a matter of choice.

.avif)

Writing the closing lines

As you start writing the end of your story, and you’re fretting about happy endings or whether you’re en route to a bad ending, think about what you want to make your reader feel. The same way as they felt when they began your first chapter? Probably not. The last impressions in your reader’s mind will be powerful, so it’s worth thinking about these final moments carefully—not just in how you tie up loose ends for your main characters, or whether you deliver an unexpected ending for your main plot, or whether your ending needs more detail. Rather, it’s worth considering the very words you choose as you end a story.

To give you some inspiration on how to end a story with a memorable final line, let’s look at how some of the great novels have concluded, along with some personal favorites from our team. Even if you haven’t read some of these books, seeing how the story ends will generally give you a nice example of the tone of the whole book and the journey that is reaching its conclusion. Ideally, they’ll leave you feeling something.

The ultimate list of the best last lines of books

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

—F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

After all, tomorrow is another day.

—Margaret Mitchell, Gone with the Wind

He turned out the light and went into Jem’s room. He would be there all night, and he would be there when Jem waked up in the morning.

—Harper Lee, To Kill a Mockingbird

The eyes and faces all turned themselves towards me, and guiding myself by them, as by a magical thread, I stepped into the room.

—Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.

—George Orwell, Animal Farm

He loved Big Brother.

—George Orwell, 1984

The old man was dreaming about the lions.

—Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea

‘I got something to tell you,’ said Keisha Blake, disguising her voice with her voice.

—Zadie Smith, NW

O God, You’ve done enough, You’ve robbed me of enough, I’m too tired and old to learn to love, leave me alone forever.

—Graham Greene, The End of the Affair

Up out of the lampshade, startled by the overhead light, flew a large nocturnal butterfly that began circling the room. The strains of the piano and violin rose up weakly from below.

—Milan Kundera, The Unbearable Lightness of Being

But that is the beginning of a new story – the story of the gradual renewal of a man, the story of his gradual regeneration, of his passing from one world into another, of his initiation into a new unknown life. That might be the subject of a new story, but our present story is ended.

—Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Crime and Punishment

And the ashes blew towards us with the salt wind from the sea.

—Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

But this is how Paris was in the early days when we were very poor and very happy.

—Ernest Hemingway, A Moveable Feast

Are there any questions?

—Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

Curley and Carlson looked after them. And Carlson said, ‘Now what the hell ya suppose is eatin’ them two guys?’

—John Steinbeck, Of Mice and Men

At that, as if it had been the signal he waited for, Newland Archer got up slowly and walked back alone to his hotel.

—Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence

The knife came down, missing him by inches, and he took off.

—Joseph Heller, Catch-22

It begins like this: Barrabás came to us by sea...

—Isabel Allende, The House of the Spirits

They were only a thin slice, held between the contiguous impressions that composed our life at that time; the memory of a particular image is but regret for a particular moment; and houses, roads, avenues are as fugitive, alas, as the years.

—Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way

He now has more patients than the devil himself could handle; the authorities treat him with deference and public opinion supports him. He has just been awarded the Cross of the Legion of Honor.

—Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary

I never saw any of them again—except the cops. No way has yet been invented to say good-bye to them.

—Raymond Chandler, The Long Goodbye

He turned away to give them time to pull themselves together; and waited, allowing his eyes to rest on the trim cruiser in the distance.

—William Golding, Lord of the Flies

She looked up and across the barn, and her lips came together and smiled mysteriously.

—John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

This stone is entirely blank. The only thought in cutting it was of the essentials of the grave, and there was no other care than to make this stone long enough and narrow enough to cover a man. No name can be read there.

—Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

Old father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good stead.

—James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

One bird said to Billy Pilgrim, ‘Poo-tee-weet?’

—Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

The offing was barred by a black bank of clouds, and the tranquil waterway leading to the utmost ends of the earth flowed sombre under an overcast sky – seemed to lead into the heart of an immense darkness.

—Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

But the horses didn’t want it – they swerved apart; the earth didn’t want it, sending up rocks through which riders must pass single file; the temples, the tank, the jail, the palace, the birds, the carrion, the Guest House, that came into view as they issued from the gap and saw Mau beneath: they didn’t want it, they said in their hundred voices, ‘No, not yet,’ and the sky said, ‘No, not there.’

—E.M. Forster, A Passage to India

‘Yes. I am giving him up.’

—J.M. Coetzee, Disgrace

It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.

—Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

‘It isn’t fair, it isn’t right,’ Mrs. Hutchinson screamed, and then they were upon her.

—Shirley Jackson, The Lottery

So in America when the sun goes down and I sit on the old broken-down river pier watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast, and all that road going, and all the people dreaming in the immensity of it, and in Iowa I know by now the children must be crying in the land where they let the children cry, and tonight the stars’ll be out, and don’t you know that God is Pooh Bear? the evening star must be drooping and shedding her sparkler dims on the prairie, which is just before the coming of complete night that blesses the earth, darkens all the rivers, cups the peaks and folds the final shore in, and nobody, nobody knows what’s going to happen to anybody besides the forlorn rags of growing old, I think of Dean Moriarty, I even think of Old Dean Moriarty the father we never found, I think of Dean Moriarty.

―Jack Kerouac, On the Road

Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood: and how she would gather about her other little children, and make their eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland of long ago: and how she would feel with all their simple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys, remembering her own child-life, and the happy summer days.

―Lewis Carroll, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.

—James Joyce, Dubliners

Some favorite final lines from the team at The Novelry

Editor Elizabeth Kulhanek counts this simple line among her favorites:

‘Well, I’m back,’ he said.

—J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King

Writing coach Emylia Hall declares this last line ‘exquisitely heartbreaking’:

But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

—George Eliot, Middlemarch

Piers Torday, writing coach for children’s fiction, chooses the heartwarming last lines from two classic novels:

It is not often that someone comes along who is a true friend and a good writer. Charlotte was both.

—E.B. White, Charlotte’s Web

It is Clarissa, he said. For there she was.

—Virginia Woolf, Mrs. Dalloway

Our Community and Events Manager, Katalina Watt, counts herself ‘forever obsessed’ with this last line...

I lingered round them, under that benign sky: watched the moths fluttering among the heath and harebells, listened to the soft wind breathing through the grass, and wondered how any one could ever imagine unquiet slumbers for the sleepers in that quiet earth.

—Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights

SFF editor Craig Leyenaar favors the final lines of three different books:

‘Darling,’ replied Valentine, ‘has not the count told us that all human wisdom was contained in these two words—“wait and hope”?’

—Alexandre Dumas, The Count of Monte Cristo

And though he tried to look properly severe for his students, Fletcher Seagull suddenly saw them all as they really were, just for a moment, and he more than liked, he loved what it was he saw. No limits, Jonathan? he thought, and he smiled. His race to learn had begun.

—Richard Bach, Jonathan Livingston Seagull

P.S. please if you get a chanse put some flowrs on Algernons grave in the bak yard.

—Daniel Keyes, Flowers for Algernon

Children’s fiction writing coach David Solomons chooses another classic:

And in the quiet of his room, Tom whispered, ‘Goodnight, son.’

—Michelle Magorian, Goodnight, Mr. Tom

Writing coach Gina Sorell chooses a very particular closing line that has always stuck with her:

And as he faded to eternal slumber, surrounded by loved ones, just feet from the sunflowers and summer moss that had helped wipe away the tumult of his first twelve years of life, he would offer four words in his final murmurings that were forever a puzzle to all that knew and loved him and surrounded him in his final moments of life, save for one who was not there, who was far beyond them all, now living in the land where the lame walked and the blind could see, who awaited him even at that moment as he drifted upward, eager to hear the news of the many adventures that had befallen him since they parted ways. It was to him that he spoke, not to them.

He called out... ‘Thank you, Monkey Pants.’

—James McBride, The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store

Editor Tash Barsby opts for the twisty line at the very end of this thriller:

I do not look at the patch of sand, roughly two hundred yards from the jetty, where a picnicking family will be starting to wonder where their youngest son is.

—Sharon Bolton, Little Black Lies

Writing coach Libby Page has a special place in her heart for this childhood classic:

At the end of the field, among the thin gold spikes of grass and the harebells and Gipsy roses and St. John’s Wort, we may just take one last look, over our shoulders, at the white house where neither we nor anyone else is wanted now.

—E. Nesbit, The Railway Children

Writing coach Andrea Stewart loves this last line:

Hazel followed; and together they slipped away, running easily down through the wood, where the first primroses were beginning to bloom.

—Richard Adams, Watership Down

Writing coach Ella McLeod has two personal favorites:

In the darkness, two shadows, reaching through the hopeless, heavy dusk. Their hands meet, and light spills in a flood like a hundred golden urns pouring out of the sun.

—Madeline Miller, The Song of Achilles

But I don’t think us feel old at all. And us so happy. Matter of fact, I think this the youngest us ever felt.

—Alice Walker, The Color Purple

.avif)

Hopefully, these wonderful last lines will give you lots of food for thought as you come to writing your own final sentence. Think about how your closing line(s) are attached to your character’s emotions or the theme of your story—or even something that ties back to the very beginning of your book. Consider the rhythm and tone of your words, and the flow of the sentence as you speak it aloud.

Plus, it never hurts to close your eyes and imagine the reader staring longingly at that final page before pressing your book to their heart and looking off into the distance.

You can do it.

Wherever you are on your writer’s journey, we can offer the complete pathway from coming up with an idea through to ‘The End.’ Our novel writing programs include personal mentorship from published authors, live classes, and step-by-step self-paced lessons to inspire you daily, and we’ll help you complete your book with our unique one-hour-a-day method. Learn from bestselling authors and publishing editors to live—and love—the writer’s life. Sign up and start today. The Novelry is the famous fiction writing school that is open to all!

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)