At the heart of literary fiction is the human experience and all it entails—our sense of time, grief, love, adventure, history, language, family, geography... We could go on. When considered this way, it’s hard not to see that, despite its reputation, literary fiction truly is for every reader.

But is it for every writer?

In this article, editor Sadé Omeje takes a deep dive into this genre, demystifying it with insight from our writing coaches and editors, as well as some examples from contemporary literary fiction.

Whether you love to read literary fiction or consider it the genre in which you’re writing (or both), this article will give you key insights into:

- Which novels typify literary fiction

- How they differ from genre or ‘commercial’ fiction

- The key essentials of what makes literary fiction

- What literary fiction is NOT (and what genre you might be writing instead)

- What makes it so important as a genre

- How literary authors get published

Before joining The Novelry, Sadé was an Assistant Editor at 4th Estate and William Collins, two imprints of HarperCollins, where she worked closely on the Sunday Times bestseller Cleopatra and Frankenstein by Coco Mellors and I Am Still With You by Emmanuel Iduma, winner of the 2022 Windham Campbell Prize. Over to Sadé...

.avif)

Literary fiction (sometimes abbreviated to ‘lit fic’) tends to be a divider of sorts, like whether you’re a plotter or a pantser, an extrovert or an introvert. But like all of these things, neither one is wrong or right.

As a genre, literary fiction is known for being a little exclusive, a hoarder of fancy prizes, and the home of ‘serious’ fiction about the human condition. It is sometimes seen as out of touch, but I personally think that’s a harsh critique. Like any genre, it has its own parameters. In popular fiction, we wouldn’t expect a crime novel to be without mystery, the same way we wouldn’t expect fantasy to be without magic.

In this sense, literary fiction is what it is, and it has its own expectations. You either enjoy it like any other genre, or you don’t! (Though I hope that, if it’s the latter, I might have changed your mind by the end of this article.)

I adore literary fiction. It pulls me in over and over again and allows me to enter the depths of another person’s being; their thoughts, feelings, and beliefs. With that pull inward, and the slight push back out at the closing of a book, my understanding of myself and the world expands or temporarily loses its fixed shape, allowing itself to be altered, changed, and reflected back to me in new and unexpected ways.

{{blog-banner-14="/blog-banners"}}

What is literary fiction? Defining the genre...

Despite its reputation for being highbrow, literary fiction is a genre of fiction that can touch every reader. But as I already mentioned, it’s not always for every writer. Let’s try to understand why that might be by asking:

- What is literary fiction—and what is it not?

- What are its ‘essentials’ (a bold word for the genre)?

- What makes it so important?

- How do writers of literary fiction get published?

Literary fiction is an exploration of human experiences, emotions, and the complexity of life through the power of language—which is why a key component of the genre is language. The prose, it sings! When compared with commercial fiction, say, it’s often more poetic, explorative, experimental, and layered with meaning and intention. I see it as an exploratory ‘drilling’ into language and its boundaries, where writers might stretch, reinvent, or cause readers to reconsider language and meaning in new and exciting ways.

Literary fiction also places a certain emphasis on character and theme over the heavily plot-driven storytelling we tend to see in more mainstream fiction (though there is certainly always some sort of plot, and literary fiction often does well and reaches more readers when there’s a plot in there). It often pushes the boundaries of conventional storytelling by experimenting with form, point of view, or the structure of novel writing itself, like A Girl Is a Half-formed Thing, Eimear McBride’s debut novel, or in novels and novellas such as Assembly by Natasha Brown and Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan—two tightly woven narratives with incredibly rich use of language and poeticism that are both less than 130 pages long.

I asked Urban Waite, one of our writing coaches, what literary fiction means for him:

Character, character, character! is my literary fiction cornerstone. So much of literary fiction is based on a character’s desires, but also the lies they tell themselves, the delusions they lead, and—with lies and delusions in mind—the problems they create for themselves along the way. This isn’t always the case, of course, but the books I find interesting have characters in them who are a little bit flawed. And in this way, they feel human. We do strange things. We let comments and words slip out. We mess up. I like to read books that lean into this, that aren’t perfect, that let us see inside someone’s soul, as imperfect as it may be.

—Urban Waite

For many of these novels, the characters are the plot. This is why, if you don’t have an interesting cast of characters or a uniquely positioned protagonist, you might struggle to make the pages feel alive and to make it feel like something is happening in the story.

If we look at some of the finalists and winners of the most prestigious literary awards in the U.S. and the U.K.—the National Book Award and the Booker Prize—most of these titles are character-driven stories. Take, for example, the multi-award-winning James by Percival Everett, the Women’s Prize for Fiction winner An American Marriage by Tayari Jones, the highly acclaimed All Fours by Miranda July, stellar debut The Safekeep by Yael van der Wouden, or the four generations of characters seen in Held by Anne Michaels.

On the other hand, you might be thinking: Don’t all great books have great characters? And didn’t you just say that literary fiction refers to theme, prose, or the ‘central question’ of the novel over character and plot?

The answer is a resounding yes!

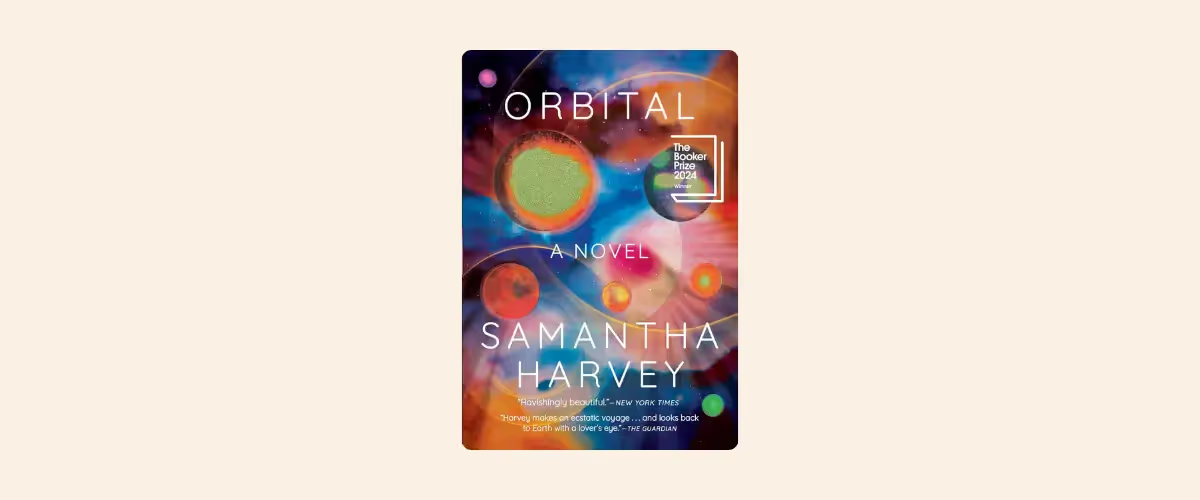

This is the case for the 2024 Booker Prize winner Orbital by Samantha Harvey. Orbital focuses more on the beauty and realism of space and humanity, and in particular, our planet and our existence within and on it, explored through the lives of six astronauts over 24 hours. Each chapter covers a single 90-minute orbit around Earth, with 16 orbits in 24 hours. Harvey utilizes the structure to reinforce the fragmented yet consistent rhythm of their days and our days, and the Earth’s continuous orbit. The prose is rich and intimate, and reads at times like a painting, with Harvey constructing clear, incredibly beautiful images of the planet, space, the subtleties of movement between her characters, and the sharpness of the dialogue.

Another literary novel, Ask Me Again by Clare Sestanovich (2024), threads together fragmentary events that make up the protagonist’s life in a philosophical, delightfully written coming-of-age story. The events themselves are less of a connected, tightly woven plot; rather, they are impressed upon us through language and a curiosity about how connection can be found through language and its subtleties.

Sestanovich’s novel explores how relationships—when viewed through prisms of class, gender, age, and location—can define us, change us, and point us toward futures we might not have imagined for ourselves. Eva is the novel’s main character, but Ask Me Again is less about her personal character development and arc, and more about the slow and steady maturing of her questions toward herself, her country, and the people in her life. Sestanovich uses questions for the chapter headings (Did You See That?, Can You Feel That?, How Could You?) as a device that creates an atmosphere of probing apprehension for the characters and the readers.

When compared with commercial fiction, say, [literary fiction is] often more poetic, explorative, experimental, and layered with meaning and intention. I see it as an exploratory ‘drilling’ into language and its boundaries, where writers might stretch, reinvent, or cause readers to reconsider language and meaning in new and exciting ways.

—Sadé Omeje

Is it literary fiction or genre fiction?

It can be tricky to work out whether your novel sits on the literary fiction shelf or elsewhere in genre fiction. Here’s a look at how literary fiction compares to some of its closest bedfellows, so you can work out where your story fits best. Remember: when you get to pitching agents, it’s essential to be sure which genre you’re aiming for.

Literary fiction vs commercial fiction

Ultimately, although literary fiction is for all readers, not all writers are writing literary fiction when they’re first starting out, even if they think they are. Often, you can start out in one genre and soon realize you’re actually writing in another, and at The Novelry, we’ve found there are a few genres that writers can often mistake their genre for. For example, there’s a difference in focus or a shift in weight distribution between commercial fiction and literary fiction.

I asked Francine Toon, editorial head of our literary fiction department and author of Pine, what she considers this difference to be, and how you can recognize when you’re not writing literary fiction.

For me, the difference between literary fiction and commercial fiction is the fact that the latter needs to cater toward a certain existing readership by providing things they love about a genre, but with a fresh and intriguing angle. When I was a literary fiction editor [at Sceptre], the question wasn’t ‘What does this book bring to the genre?’ but ‘Does this book have a chance at winning a prize?’ That might sound like a high bar, but it’s one thing that drives sales in an increasingly difficult area of the market. On a more tangible level, I was looking for writing that had a good, consistent sense of style (whether that be poetic, pared back, ‘voicey,’ or something else) and a story that felt ‘ambitious’ enough in terms of stakes and scope to stand out from the crowd.

—Francine Toon

Prizes are a key player when it comes to literary fiction. Not only in the commercial sense, since they boost sales and increase writer recognition, but they’re a point of reference for emerging trends or voices in the literary space. They exist to recognize and reward the writer’s craft; their use of theme, character, prose, style, and many other considerations.

In the U.S., for example, some of the prizes editors might consider when acquiring a literary fiction novel are:

- The National Book Award

- The Pulitzer Prize

- The PEN America Literary Awards

- The NAACP Image Awards

- The George Plimpton Prize for Fiction

Meanwhile, in the U.K., editors will be considering:

- The Booker Prize

- The Women’s Prize for Fiction

- The Nero Book Awards

- The RSL Ondaatje Prize

- The Orwell Prize

- The Goldsmiths Prize

- The Betty Trask Prize

It’s always worth knowing what prizes exist in your country, as it can be a helpful way to determine for yourself—and your future agent(s) and editor(s)—where your novel might sit in the market. Take a look through the lists of recent winners, along with the longlisted and shortlisted titles. Maybe your writing style or the premise of your story is trying to bring a fresh and intriguing angle, like a new take on a romance or a ‘twist’ on a thriller.

Although literary fiction is for all readers, not all writers are writing literary fiction when they’re first starting out, even if they think they are.

—Sadé Omeje

If you’re a writer of literary fiction, then, naturally, you’ll be a reader of literary fiction, too. Reading across these prizeworthy titles is crucial for broadening your knowledge of the genre and market. But more importantly, it strengthens your appreciation for the work of your fellow writers and develops your tastes across a range of styles and voices. I would always recommend reading outside of your genre, too—which might incidentally lead you to your true genre, if your literary novel is actually more commercial or upmarket.

Literary fiction vs upmarket fiction and book club fiction

How does ‘lit fic’ contrast with, say, upmarket fiction? Josie Humber, our editorial head of upmarket and book club fiction, says:

To me, upmarket fiction sits in that sweet spot between commercial and literary fiction. If commercial fiction is plot- and character-focused, and literary fiction is language- and theme-forward, then upmarket fiction lands somewhere between the two. Upmarket novels tend to still have a page-turning quality to their plotting and a killer hook, but with language that’s elevated and considered, yet accessible. While less likely to win a Pulitzer than its literary counterpart, you’ll see upmarket fiction novels securing places alongside women’s fiction titles as a Reese’s, Jenna’s, or Oprah’s Book Club pick.

—Josie Humber

How to write literary fiction: what it is and what it isn’t

We’ve covered five key elements of what it means to write in this genre:

- Unique character? ✅

- Rich idea? ✅

- Strong voice? ✅

- Interesting theme? ✅

- Fresh or experimental style or structure? ✅

But which qualities are not considered to be literary fiction essentials? If your novel has any of these, it’s a clear sign you’re writing in another genre:

- Plot-driven stories centered on solving crimes or murder mysteries ❌

- Fast-paced thrillers or horror with frightening, gory, or violent elements ❌

- Stories that follow specific romance ‘beats’ ❌

- Zeitgeist or potentially taboo topics that make room for lots of discussion and debate ❌

- Young adult themes with the Young Adult market in mind ❌

If you’re confident that your novel is still sitting comfortably in the literary fiction basket after running it past that checklist, let’s move on to look at what else might be considered an essential component of the genre.

Plot-driven or theme-driven?

Well, there are two things I want to explore a little more: theme and ambiguity. As Josie said, literary fiction is theme-forward, but what does that mean? Your theme is often the central ‘spine,’ as we say at The Novelry, that everything rests on. The theme is the question the author is asking in their novel, over and over again, and in this genre, it is often asked without a clear answer in return.

These themes are frequently considered and explored as big ideas—questions about existence, identity, time, morality, and society. They’re often open-ended, too, leaving readers room for interpretation rather than providing clear-cut answers. Which brings me to ambiguity...

Unlike genre fiction, which typically follows a clear structure with a resolution, literary fiction often embraces ambiguity. Books like The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro leave readers with a sense of melancholy and reflection, while in books like Piranesi by Susanna Clarke, the ending is intentionally vague, allowing readers to form their own interpretations of Piranesi’s fate and the nature of his new reality.

When I asked what literary fiction means for her, writing coach Mahsuda Snaith said:

In commercial fiction, finding out what happens in the story is paramount, while in literary fiction, the story is pieced together by the reader, with no promise that it will be overtly explained or tied up neatly. It is the language, character, and themes that sweep you along in these types of books, though the story that is slowly revealed is a vital element, too. For me, a good literary novel not only makes me think, it makes me question the world around me and therefore rethink.

—Mahsuda Snaith

Two books Mahsuda has recently loved that do this well are The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka and Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan.

Both deal with the Sri Lankan civil war in two very different stylistic and individual ways that are both striking and memorable.

—Mahsuda Snaith

A brief history of literary fiction

Literary fiction has been shaping the way we understand humanity for decades, from Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes, first published in 1605, to classic novels such as:

- Great Expectations by Charles Dickens (1861)

- 1984 by George Orwell (1949)

- To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee (1960)

- The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison (1970)

- Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe (1958)

- Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie (1981)

- The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood (1985)

As a style of writing, it is often used as a point of reason—the laying out, unpacking, repacking, examining, and analysis of a viewpoint, perspective, or argument. Essentially, it’s a theme that is ‘for’ or ‘against’ or is exploring that nebulous place in between. It challenges our prejudices and assumptions, sparks conversations, and deepens our understanding of human nature, fostering empathy, compassion, and hope. And because literary authors are often attempting to take on the task of confronting humanity, oppression, politics, governments, and movements—and their problems, curiosities, pitfalls, hopes, and dreams—the ambitious, mammoth undertaking this poses often boils down to, without a doubt, the existence of a strong authorial or character voice.

[Literary fiction] challenges our prejudices and assumptions, sparks conversations, and deepens our understanding of human nature, fostering empathy, compassion, and hope.

—Sadé Omeje

What we mean when we talk about ‘voice’

‘Voice’ is sometimes too simplified a word to describe what we mean and what we feel when prose speaks to our hearts and minds directly. It’s a blend of many things. The technical syntax arrangement of words and sentences, to the unique perspective brought to the work; the author’s use of tone, vocabulary, and style. Voice allows the reader to be fully immersed in the narrative, and once found, practiced, or established, it’s arguably the literary writer’s most powerful tool.

It is no surprise, then, that of the list of books mentioned above, all of them have been either banned or challenged over the years for their content. Yet, despite this, among these authors and the many that came before, during, and after them, their writing, their ideas, and their stories continue to endure, influencing literary movements from realism to modernism to postmodernism and defining literary fiction across generations.

I asked writing coach Tara Conklin what she admires about literary fiction and why voice is so essential to this genre, more so than it might be if you’re writing in another genre:

I think what I love most about literary fiction, and what draws me back to that genre (both as a reader and a writer), is voice. And this can be understood in different ways—either a strong, compelling character’s voice that I haven’t heard before, or a writer with a particular prose style that is beautiful to read. Voice too goes to the writer’s areas of concern and being able to trust that when they turn their attention to a subject, I’ll want to read that book. I think of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie—her books are all so different, but I trust that I’m in expert hands with her. She’s so smart and curious that I automatically want to read whatever she’s writing about. And character voice—in The Safekeep, Isabel’s voice is one I hadn’t heard before, and Yael van der Wouden’s authorial style was so pure and clean, I would have followed Isabel anywhere.

—Tara Conklin

Literary fiction in the publishing industry

In the world of books, publishing is dominated by the Big Five (Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon and Schuster, Macmillan, and Hachette), with whom our trusted literary agents all work closely. And yet, things are constantly changing. Self-publishing is becoming more and more popular each year, and independent book publishers are continuing to grow and establish firmer footholds in their positions as long-standing publishers.

To me, ‘indies’ are the bedrock of publishing and of the entire business of reading itself, often working closely with booksellers in independent bookstores, where we all find ourselves losing track of time, buying one book too many, and seeking out new and exciting recommendations—or even more intriguing, forgotten, lesser-known books that are (as is the way of things) experiencing a literary revival.

What independent publishers mean to literary fiction

Independent publishers offer vital, important spaces for diverse voices and genres to emerge, and their nimble, more flexible nature allows for a level of risk-taking that larger publishing houses tend to avoid. They’re often known for publishing books that might be considered too niche or risky for major publishers, such as when And Other Stories published Deborah Levy’s Swimming Home in 2011, shortlisted for the 2012 Booker Prize.

And Other Stories also had two books nominated for the 2025 International Booker Prize: Ibtisam Azem’s The Book of Disappearance, and the eventual winner, Heart Lamp by Banu Mushtaq. Their 2024 titles alone were the recipients of countless wins, shortlists, or longlists—a testament to the importance of literary prizes when it comes to literary fiction.

Independent publishers often champion authors and genres that might otherwise be overlooked. They seek out books that push boundaries of form and explore different ways of telling stories, leading to a variety of books available for readers from a variety of different backgrounds and places.

It is not uncommon for writers to start with smaller, independent publishers and then later move on to larger book deals with a Big Five Publisher, such as Irenosen Okojie, from Jacaranda Books to deals with Hachette, or Deborah Levy, from And Other Stories to deals with Penguin Random House. Nor is it uncommon for well-established authors to remain with independent publishers for many of their books, such as Annie Ernaux with Fitzcarraldo Editions, or Greg Hewett with Coffee House Press. When it comes to publishing, it’s all about finding the right home for your novel and you as a writer, with the main objective being to get the story out there and into the reader’s hands.

Literary fiction remains a powerful force in storytelling, offering readers not just stories but experiences that challenge, inspire, and endure through time. Independent publishers, therefore, are often the first, early homes for many literary fiction authors. I’ve mentioned a few already, but here’s a short selection (because there are so many, which is great to be able to say) of independent publishers of literary fiction across the U.S., U.K., and Canada:

Some independent publishers in the U.S.A.

Graywolf Press: A nonprofit literary publisher of poetry, fiction, non-fiction, and work in translation, with a mission to publish risk-taking, visionary writers who transform culture through literature.

Tin House: A publisher of award-winning books of literary fiction, non-fiction, and poetry, with a focus on writing that is artful, dynamic, and original.

Coffee House Press: An internationally renowned nonprofit publisher of literary fiction, essays, poetry, and other work that doesn’t fit neatly into genre categories, calling for adventurous readers, art enthusiasts, community builders, and risk takers.

Catapult: Publishers of literary fiction and artful narrative non-fiction that engages with their coined term ‘Perception Box,’ the metaphor they use to define the structure and boundaries of how we see others in their full humanity, and invites new ways of seeing and being seen.

Bellevue Literary Press: The first and only nonprofit press dedicated to literary fiction and non-fiction at the intersection of the arts and sciences.

Verso Books (also in the U.K.): One of the largest independent, radical publishing houses in the English-speaking world, publishing over 100 books a year.

Some independent publishers in the U.K.

And Other Stories: A publisher of mainly contemporary writing, including many translations. They select books that make you think and are able to last the test of time, with an aim to push people’s reading limits and help them discover authors of adventurous and inspiring writing.

Fitzcarraldo Editions: An independent publisher specializing in contemporary fiction and long-form essays, with a focus on ambitious, imaginative, and innovative writing, both in translation and in the English language.

Canongate: An award-winning independent publisher based in Edinburgh and London, known for its groundbreaking, eclectic, and endlessly energetic publishing.

Daunt Books: An imprint dedicated to publishing brilliant works by talented authors from around the world. Whether reissuing beautiful new editions of lost classics or publishing debut works by fresh voices, their titles are inspired by the Daunt Books bookstores themselves and the exciting atmosphere of discovery that is found in a good bookshop.

Atlantic Books: An independent publishing house with a worldwide reputation for quality, originality, and breadth, and which includes fiction, politics, memoir, and current affairs.

Jacaranda Books: An award-winning, diverse-owned independent publisher and bookseller, dedicated to promoting and celebrating brilliant diverse literature.

Some independent publishers in Canada

Grove Atlantic: An independent literary publisher with seven different imprints within it, known for publishing a wide breadth of genres and prize-winning authors from all over the world.

W.W. Norton and Company: A publisher proud to publish ‘Books That Live,’ books that educate, inspire, and endure.

House of Anansi: A publisher that continues to break new ground with award-winning and bestselling books that reflect the changing nature of the country and the world.

Take some time out to have a look at these independent publishers, or look up the ones local to you, and, with any luck, you’ll discover a literary fiction author who might just become a new favorite of yours.

Wherever you are on your writing journey, we can offer the complete pathway from coming up with an idea through to ‘The End.’ With personal coaching, live classes, and step-by-step self-paced lessons to inspire you daily, we’ll help you complete your book with our unique one-hour-a-day method. Learn from bestselling authors and publishing editors to live—and love—the writing life. Sign up and start today. The Novelry is the famous fiction writing school open to all!

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)