Any tale of any kind told to humans by humans is and has ever been a morality tale. Before the novel, we had the morality play or allegorical play, with personified virtues and villains exhorting good behavior to a crowd. Earlier still, a single bard may have recited a dramatic work solo, traveling around the country telling tales of tortured anguish for the baddies, and life lessons that everybody could incorporate into their own worldview.

And the morality tale remains strong, a lingering ghost within literature that inspires us to explore modern marriage, cancel culture, high school bullies, and countless other twenty-first-century phenomena. Often, a story gathers momentum thanks to the moral questions it explores.

The power of the morality tale

‘There was a man who...’ This person has a flaw, a failing, either moral (a tendency that will bring them and others misery) or cosmic (a hole in his or her fortune). They can’t see it, but they are offered as an example to humanity of a singular failing. Robbie Burns was right to bemoan the fact that we cannot see ourselves as others see us. It would save us a lot of grief. But a morality tale is the closest we ever come, like Narcissus, to gazing at our own reflection.

The action of the book sets the flaw straight. The story begins with their error as the context for the story, a shadow cast over the context of the plot. With drama afoot from the outset, the flaw exists to create chaos among the cast. To move to the fabled golden state, or happy ending, the events of the story gather momentum and, generally, a salutatory friendship develops to guide our poor innocents toward a friendly escape from unhappiness.

At the dénouement, the protagonist stands corrected.

So, your hook must give us the presence of a person with a flaw and hint at the outcome—that, thanks to the existence of forces friendly or fierce, this flaw will likely be corrected.

That is a tale, and in essence, every tale is a morality tale. Because every human wants to get better and be happier, and we read by example to find out how.

From Aesop to Orwell

Orwell’s innocent eye was often devastatingly perceptive... a man who looked at his world with wonder and wrote down exactly what he saw, in admirable prose.

—John Mortimer, Evening Standard

The morality tale, as we recognize it, began with Aesop.

Aesop’s fables were characterized by their brevity and clarity and by the inclusion of an explicit moral at the end, which summarized the lesson illustrated by the story. Showing human values through animal characters allowed readers to examine their behavior from a distanced perspective.

After The Epic of Gilgamesh (1990 BC) comes The Iliad and The Odyssey (eighth century BC), then it’s over to Aesop, who lived from around 620 to 564 BC. Simple, effective morality tale-telling begins here, with his form like the DNA of our understanding of the purpose of fiction.

The purpose of fiction is to tell the truth in the way that we are most likely to receive it. Sometimes, a refreshingly honest approach can be provided by the saucy innocence of an animal! You can quibble over how the world was created all you like, but you can’t argue with a fox and a crow haggling over a piece of cheese. Because it is not supposed to be literal, the allegory bypasses our skepticism.

That we have been raised on this understanding is still evident in our turns of phrase derived from Aesop (see below).

The morality tale and story structure

The basic structure of a fable is the basic story structure.

Aesop’s stories were probably written down a few centuries after he lived, so this story structure is about as elemental as it gets and might help you turn your hook.

- Flaw of protagonist made plain

- Intervention of another party, in conflict

- Due desserts served, and either restoration of moral sense or crushing defeat

George Orwell’s Animal Farm

Here’s Orwell’s premise for Animal Farm, written in his own words.

Notice how he begins with the moral, and the publishers append the ‘reality’ of the fictional format.

It is the history of a revolution that went wrong – and of the excellent excuses that were forthcoming at every step for the perversion of the original doctrine.

—George Orwell, written for the first edition of Animal Farm, 1945

His simple and tragic fable, telling of what happens when the animals drive out Mr. Jones and attempt to run the farm themselves, has since become a world-famous classic of English prose.

Here is the hook ascribed and rubbed smooth by generations of readers:

George Orwell’s fable of a workers’ revolution gone wrong.

In a plain allegory, fairy tale, or fable, the IRONY is the format.

I like animals.

—George Orwell

Orwell’s take on the morality play

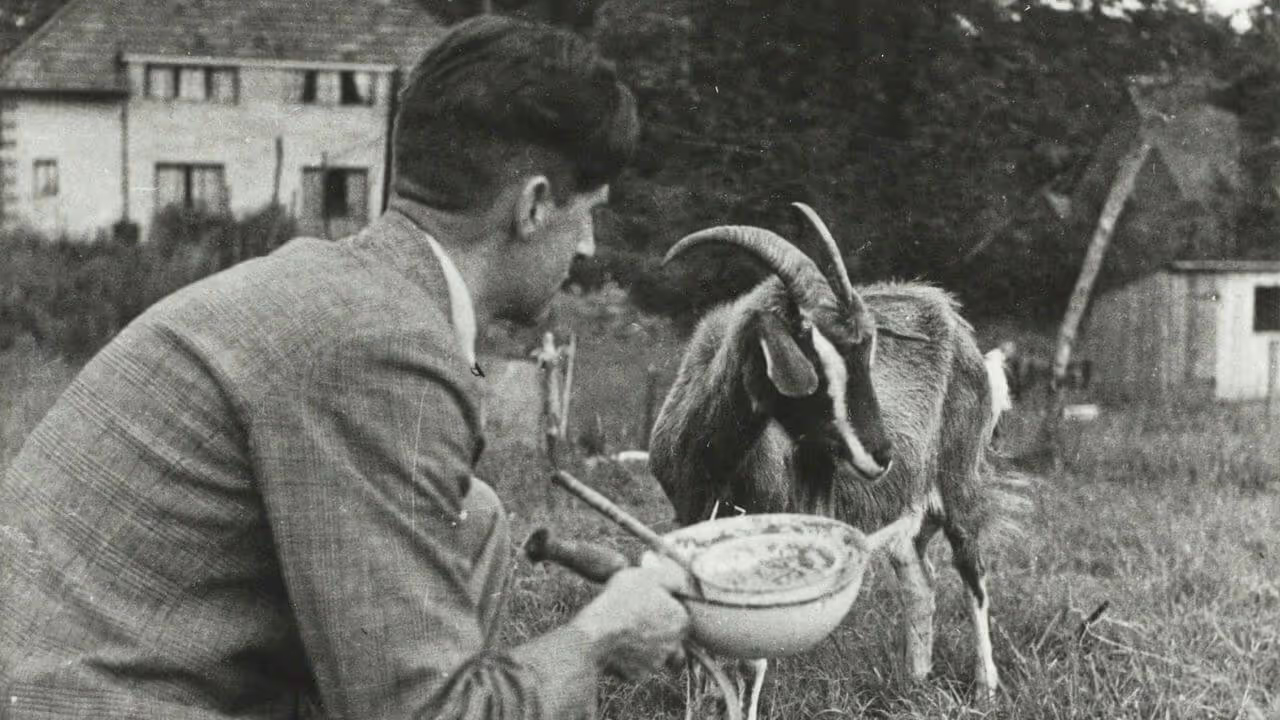

Orwell wrote Animal Farm in three months, finishing in February 1944. It’s just shy of 30,000 words.

Orwell’s happiest years, although he was suffering terribly from terminal TB, were those which—enriched by the runaway sales of Animal Farm, which was his first bestseller—he spent on his farm proper, Barnhill, on the Hebridean island of Jura.

From a piece by John Sutherland:

In the fable’s controversial conclusion the pigs – now owners of a highly profitable enterprise (for them and their dogs) – make peace with their ‘fellow’ human farmers. The animals look, in perplexity, through the windows of the farm-house.

—John Sutherland

The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.

—George Orwell, Animal Farm

The new guiding slogan for the future of the farm is: ‘All Animals Are Equal But Some Animals Are More Equal Than Others.’

The initial response to Orwell’s morality tale

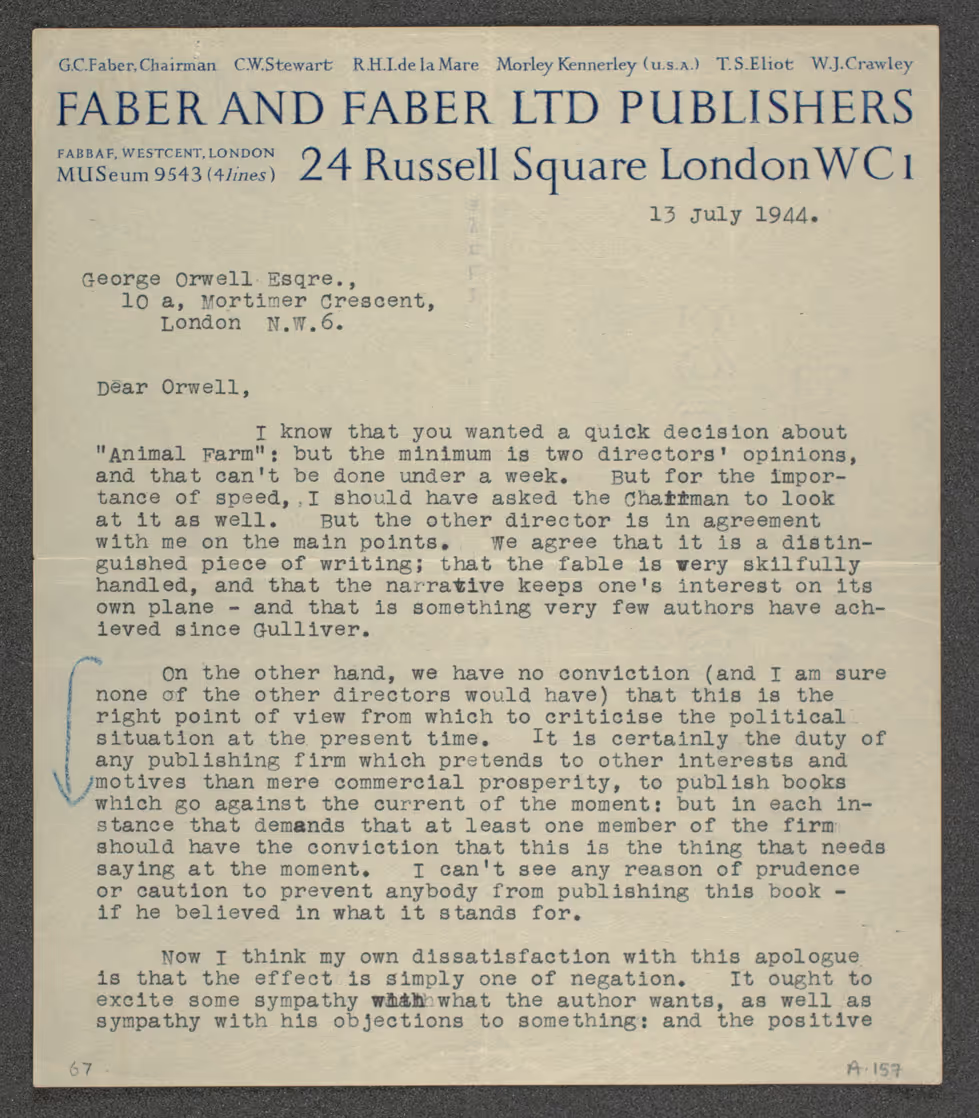

A draft of what Orwell called his ‘Fairy Story’ was finished in the summer of 1944 and submitted to his publisher, Victor Gollancz. Gollancz was an old-time communist and rejected the book by return of post.

Other publishers were reluctant, post-Stalingrad, to launch something so virulently anti-Soviet. The British, at this period, loved ‘Uncle Joe’; he was, as Churchill put it, tearing the guts out of the Nazi Empire while the allies were preparing, relatively bloodlessly, their second front.

Soviet losses in World War II (which Russians called the ‘Great Patriotic War’) were massive—tens of millions more than the Allies’ casualties.

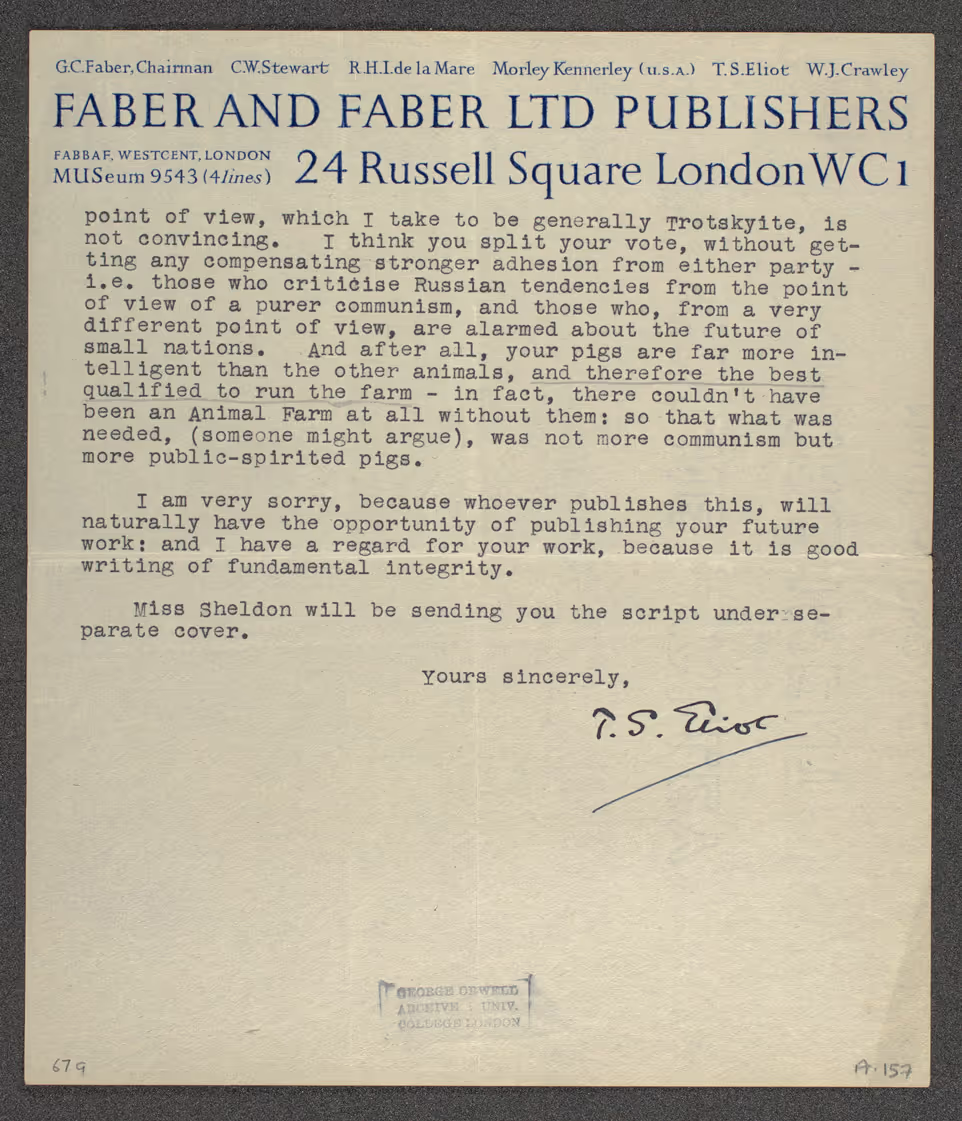

T.S. Eliot at Faber, to whom Orwell next submitted Animal Farm, praised the clear prose but felt, in his usual way, that since the pigs were the most intelligent beasts, they should indeed run things. What the farm needed was more benign piggery.

Five American publishers were uninterested. It was too English. And too anti-Soviet.

Animal Farm had to await the onset of the Cold War (a term Orwell invented). It was finally published in August 1945, as the Iron Curtain was about to fall across Europe. Once the book was out, the money flooded in.

Animal Farm was not, in its life to come, merely a fable: it was destined to become a pre-emptive weapon in the Cold War: something Orwell never intended. Over the following years, Animal Farm was disseminated behind the Iron Curtain as black propaganda.

The CIA covertly acquired the subsidiary rights to Animal Farm from Orwell’s second wife and widow, Sonia. The film was produced in England and released in 1954, the ending radically changed to predict the eventual overthrow of swine–human totalitarianism by the unquenchable forces of Western democracy. It was a wholly non-Orwellian ‘happy’ ending.

For your happy ending, come on over to the online creative writing courses at The Novelry and start writing your morality tale today with The Classic Storytelling Class.

Could you use a morality tale in your writing?

In a fantasy, or a classic novel, the flaw is reversed by magic—either hocus pocus, nature, or divine intervention—to become a virtue. In every genre of fiction, conflict plays a part, requiring the protagonist to confront what was hitherto a blindspot.

The writer gets to play God in a morality tale, safely keeping their own flaws out of sight, to use as material for the most winsomely self-deprecating form of fiction.

Which morality tale could you draw from?

To stir your creativity, let’s think about the morality tale you could infuse into your writing. It could be a great way to add another level of meaning to your writerly creation, or deliver some important revelations to your characters.

Quality, not quantity: from the tale ‘The Lioness and the Vixen’

A mother fox and lioness were boasting to each other about their young. The fox pointed out that where she gave birth to a litter of cubs each time, the lioness had only one.

‘But that one is a lion,’ responded the lioness.

Honesty is the best policy: from the tale ‘Mercury and the Woodsman’

A woodsman lost his axe in a river, and Mercury (the one with the wings on his shoes) appeared to retrieve it.

Mercury offered the woodsman an axe made of silver and another made of gold, before offering the man his own. Since the man admitted that the first two were not his, he was given all three axes as a reward.

When a friend heard this story, he dropped his own axe into the same river. Smart. Mercury appeared again but this time the friend claimed the golden axe as his own, which disgusted the god so much that he returned all three tools back to the bottom of the river, leaving the man empty-handed.

Pride comes before a fall: from the tale ‘The Eagle and the Cockerels’

Two cocks were fighting for control of a roost. When it was over, the loser of the battle went and hid himself in a dark corner while the winner climbed atop the barn and began to crow. The winner was promptly snatched up by a hungry eagle.

To take the ‘lion’s share’: from the tale ‘The Lion, the Fox, and the Ass’

A lion, a fox, and an ass went hunting together and set to divide the spoils of their efforts between them.

First, the ass divided the goods into three even piles, at which point the lion attacked and devoured him, then asked the fox to divide the food.

The fox, taking a lesson from the ass, gave the lion nearly all of the game and set aside a meager portion for himself. This pleased the lion, who then allowed the fox to live.

Don’t count your chickens before they are hatched: from the tale ‘The Milkmaid and Her Pail’

A farmer’s daughter was musing about the value of the milk she carried in the pail atop her head and began planning to use the profits to buy enough eggs to start a poultry farm.

Eventually, her wild mind led her to ponder using the spoils of her poultry farm to buy a fancy gown for the fair.

As the girl imagined how the boys would flock to her in her sparkling new duds, she tossed her hair, sending the pail of milk and all of her dreams to the dirt below.

Look before you leap: from the tale ‘The Fox and the Goat’

A fox found himself trapped in a well and so he coaxed a goat down with him into the water below.

When the goat reached the bottom of the well, the fox climbed on his back and out of his prison, leaving the goat to suffer his fate alone.

A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush: from the tale ‘The Hawk and the Nightingale’

A nightingale was caught in the talons of a hawk and pled for his life. He said that the hawk ought to let him go and pursue much larger birds that might have a better shot at slaking his hunger.

‘I should indeed have lost my senses,’ said the hawk, ‘if I should let go food ready to my hand, for the sake of pursuing birds which are not yet even within sight.’

And he ate him.

One good turn deserves another: from the tale ‘The Serpent and the Eagle’

A snake and an eagle were locked in a life-and-death battle. A countryman came upon them and freed the eagle from the serpent’s grasp.

As retribution, the snake spat venom into the man’s drinking horn and, as he went to drink, the grateful eagle knocked the poisoned drink from his hand and onto the ground below.

Fair-weather friends are not much worth: from the tale ‘The Swallow and the Crow’

A swallow and a crow were arguing over who had the superior plumage. The crow ended the discussion by pointing out that, though the swallow’s feathers were pretty, his kept him from freezing during the winter.

To have ‘sour grapes’: from the tale ‘The Fox and the Grapes’

A fox came across a bunch of grapes hanging from a trellis high above. Try as he might, he just couldn’t reach them.

As he gave up on the fruit and began to walk away, he said to himself, ‘I thought those grapes were ripe, but I see now they are quite sour.’

Slow and steady wins the race: from the tale ‘The Tortoise and the Hare’

The turtle wins the race despite the hare’s incredible speed.

A man is known by the company he keeps: from the tale ‘The Ass and His Purchaser’

A man looking to purchase an ass took one home on a trial basis and released him in the pasture with his other donkeys.

When the new addition took an instant liking to the laziest ass of the bunch, the farmer yoked him up and led him straight back to the vendor, saying that he expected the new donkey would probably just turn out as worthless as his choice of companion.

Other important revelations your characters might have

And here are a few others for your consideration...

- Familiarity breeds contempt.

- Avoid a cure that is worse than the disease.

- Don’t believe everything you hear.

- Save for a rainy day.

- Yield to all and you will soon have nothing to yield.

- Fine feathers don’t make fine birds.

- Liars often set their own traps.

- One who steals has no right to complain if he is robbed.

- It is easy to be brave from a distance.

- Each person has his strong point.

- It is foolish to try to imitate the skills of others.

- It pays to be prepared.

- It is possible to have too much of a good thing.

- Little friends may prove great friends.

- Misfortune tests the sincerity of friends.

- No act of kindness, no matter how small, is ever wasted.

- Please all and you will soon please none.

- If you can’t say anything nice, then don’t say anything at all.

- Don’t kill the goose that lays the golden egg.

- Gratitude is the sign of noble souls.

- He that is hard to please may get nothing in the end.

- It pays to be content with your lot.

- Don’t pretend to be something you aren’t.

- Honesty is the best policy.

- You can fool people some of the time, but you can’t fool them all of the time.

- A crust in comfort is better than a feast in fear.

- All of us, the great and the little, have need of each other.

- Vices are their own punishment.

{{blog-banner-2="/blog-banners"}}

Welcome home, writers. Join us on the world’s best creative writing courses to create, write and complete your book. Sign up and start today.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)